Field geology – the art of studying rocks and landscapes in their natural environment – is a cornerstone of how geoscientists unravel Earth’s story. There’s something profoundly instructive about geological fieldwork: getting your boots dirty, hammer in hand, and observing geology up close. Whether you’re a student hitting the outcrops for the first time, a professional geologist doing field mapping, or an outdoor enthusiast curious about the ground beneath your feet, fieldwork is where classroom theory meets real-world practice. This guide offers essential tips and tools for successful fieldwork in geology, blending practical preparation (gear, safety, logistics) with some philosophical insights on what the field experience teaches us. Consider it a friendly chat with a well-traveled geologist – smart and conversational – sharing advice as if over coffee with an intelligent friend. By the end, you should feel motivated and prepared to embark on your own geological fieldwork adventure. Let’s dive in!

Gearing Up: Essential Tools and Gear for Field Geology

One of the first rules of field geology is simple: be prepared. Having the right gear and geology field tools can make all the difference in your comfort and success outdoors. You don’t need a truckload of gadgets – just the essentials to stay safe, make observations, and collect data. Here’s a checklist of must-haves before you head out:

- Clothing and Day Pack: Sturdy, broken-in hiking boots (to protect your feet and ankles on rough terrain) and durable long pants are a must. Wear layered clothing (a long-sleeve shirt for sun and abrasion protection, plus a warm layer or rain jacket) so you can adapt to changing weather[1]. A wide-brimmed hat and sunglasses will shield you from sun, and you should carry at least 2 liters of water (hydration is non-negotiable!) along with lunch and snacks[1]. All of this goes into a comfortable daypack/backpack that you’ll carry in the field.

- Field Notebook and Stationery: Geology happens on the rocks, not on a laptop. Carry a weatherproof field notebook (the popular “Rite in the Rain” notebooks are great) and plenty of pencils[2]. Jotting detailed notes and sketching outcrop diagrams or maps is fundamental – you’ll be surprised how often your scribbles become invaluable later. Pro tip: use a harder pencil lead (e.g. 2H) for mapping so it doesn’t smudge, and bring colored pencils or pens to highlight different rock units or features on your map.

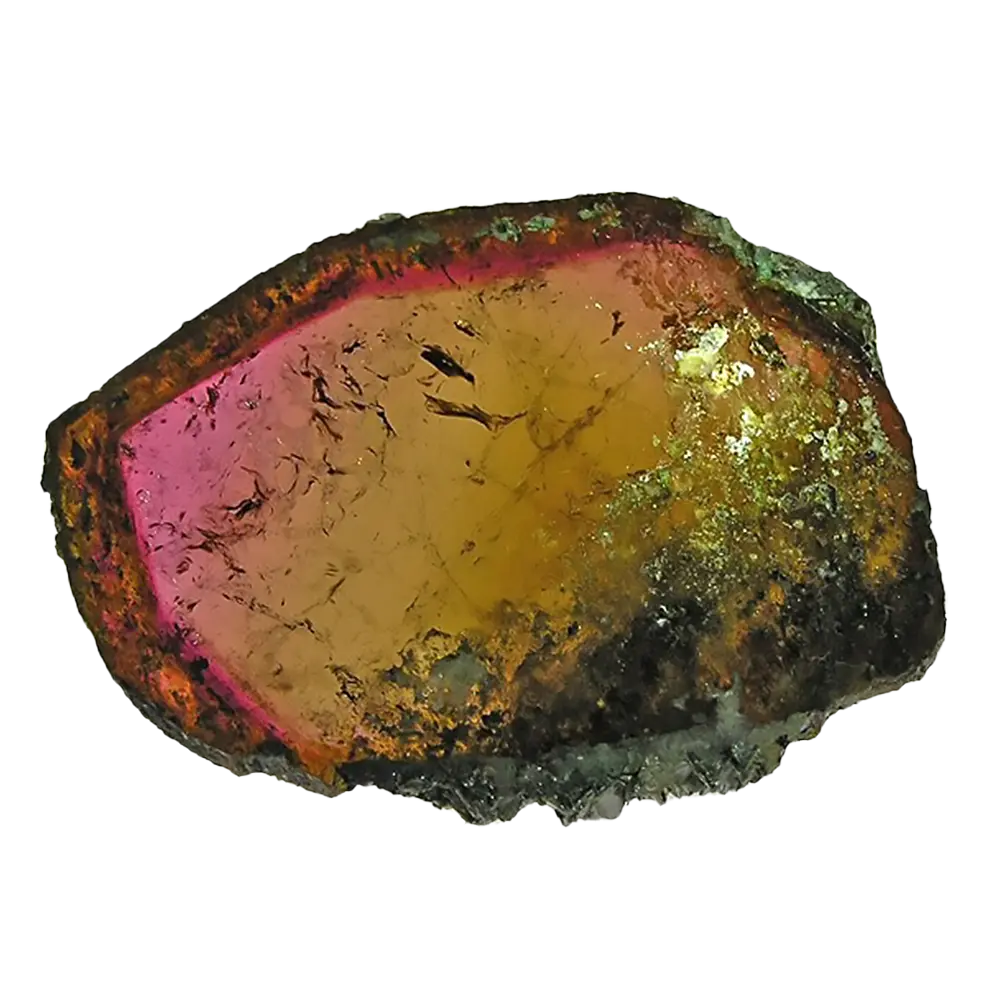

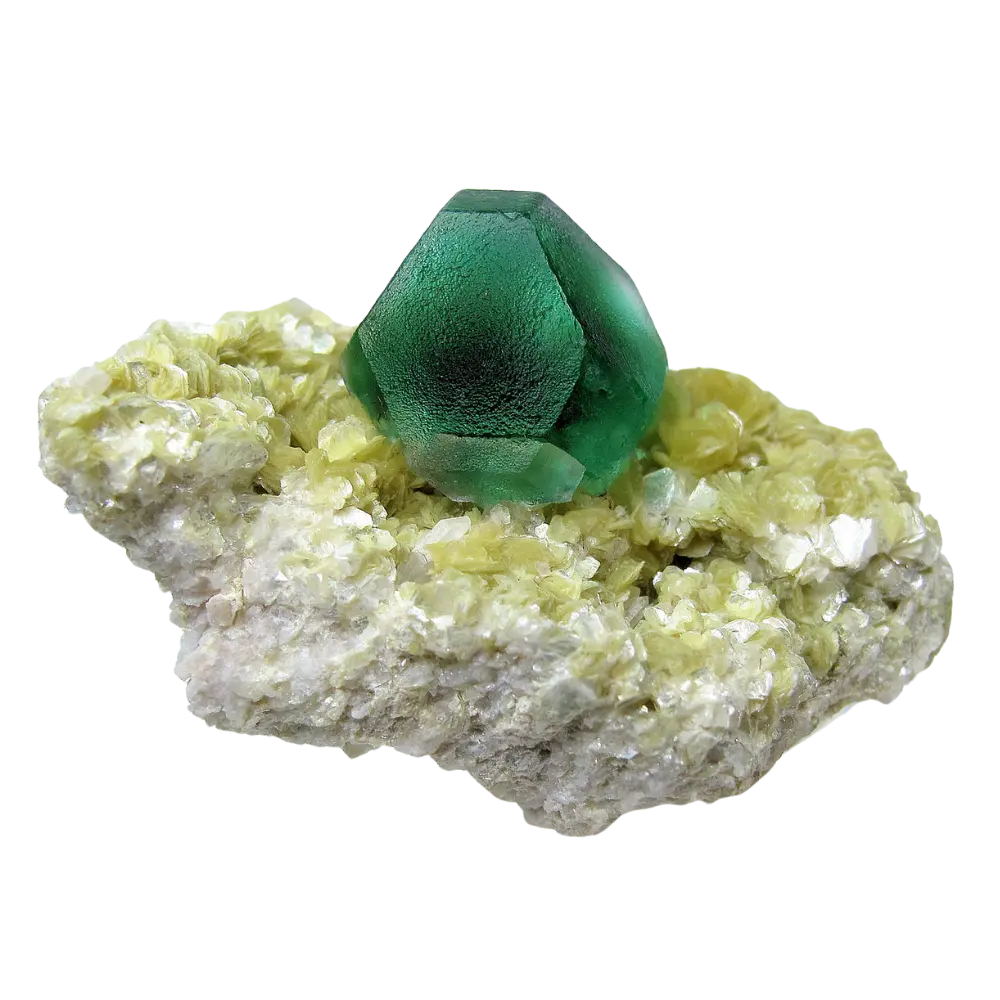

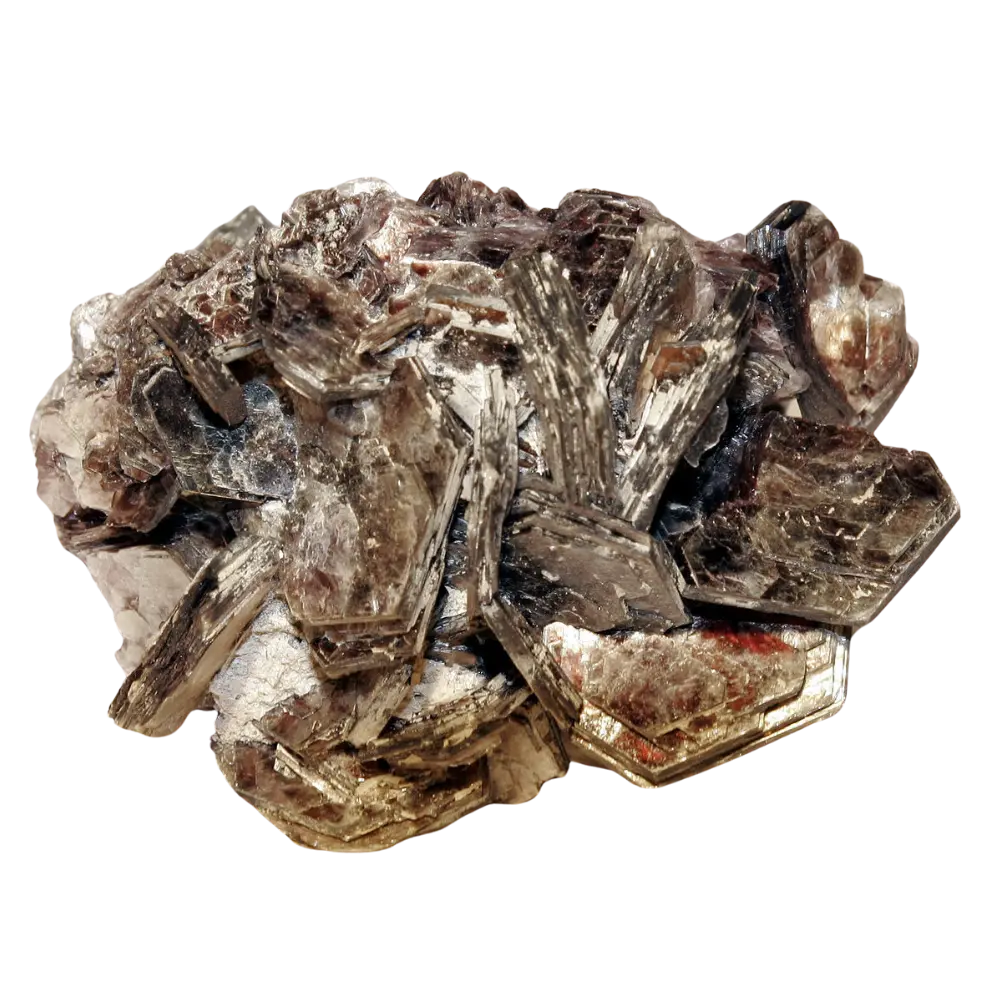

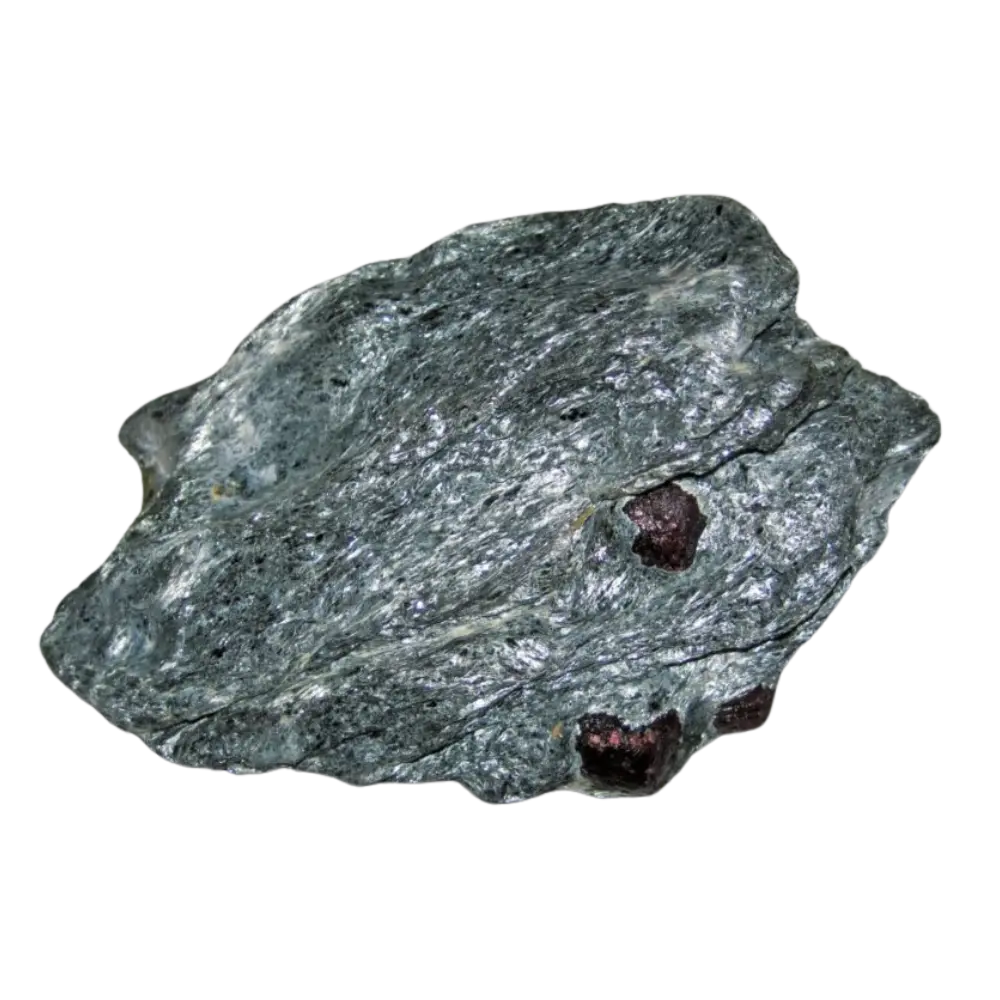

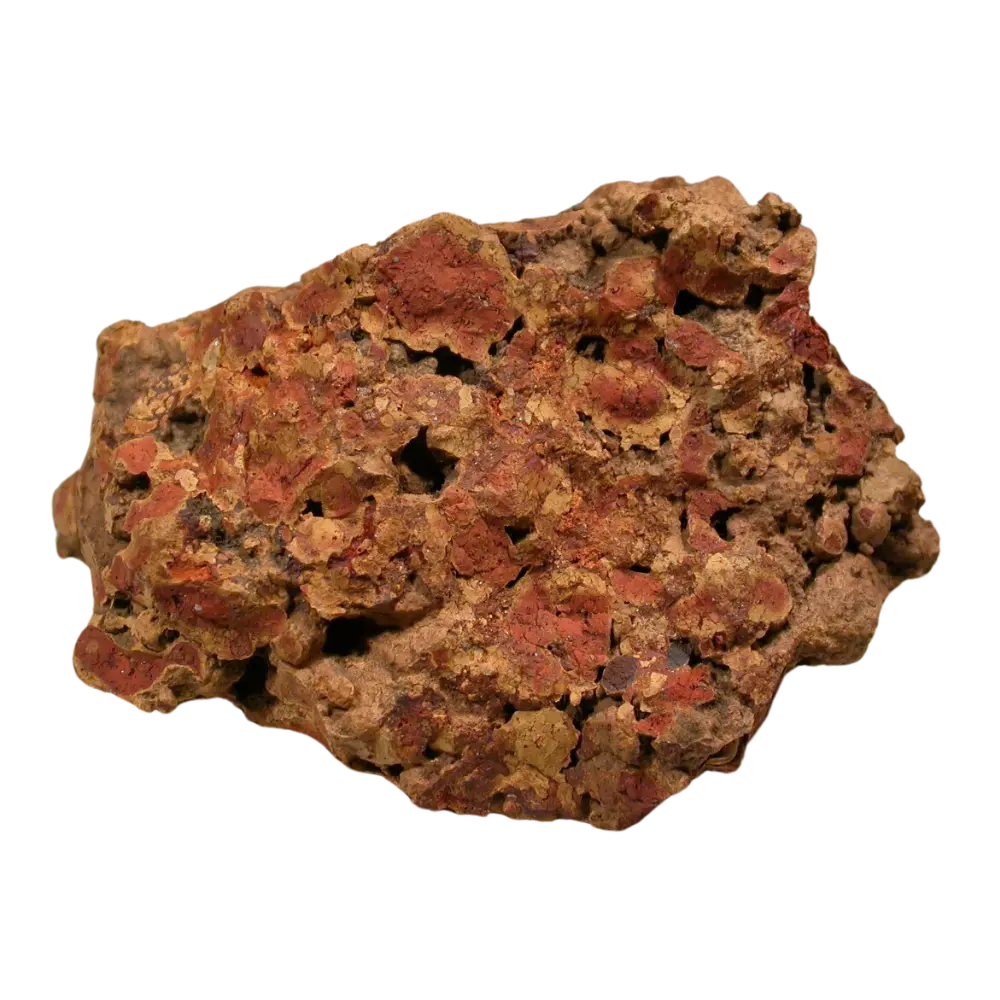

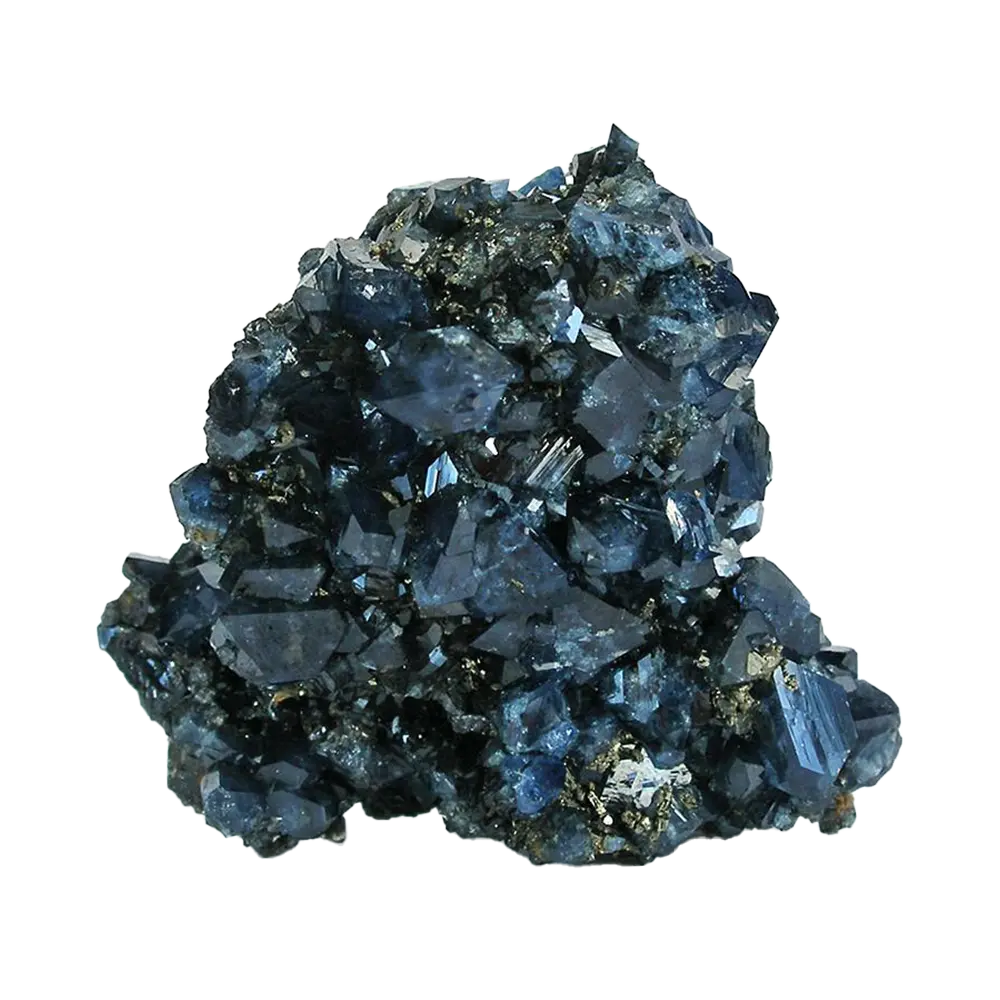

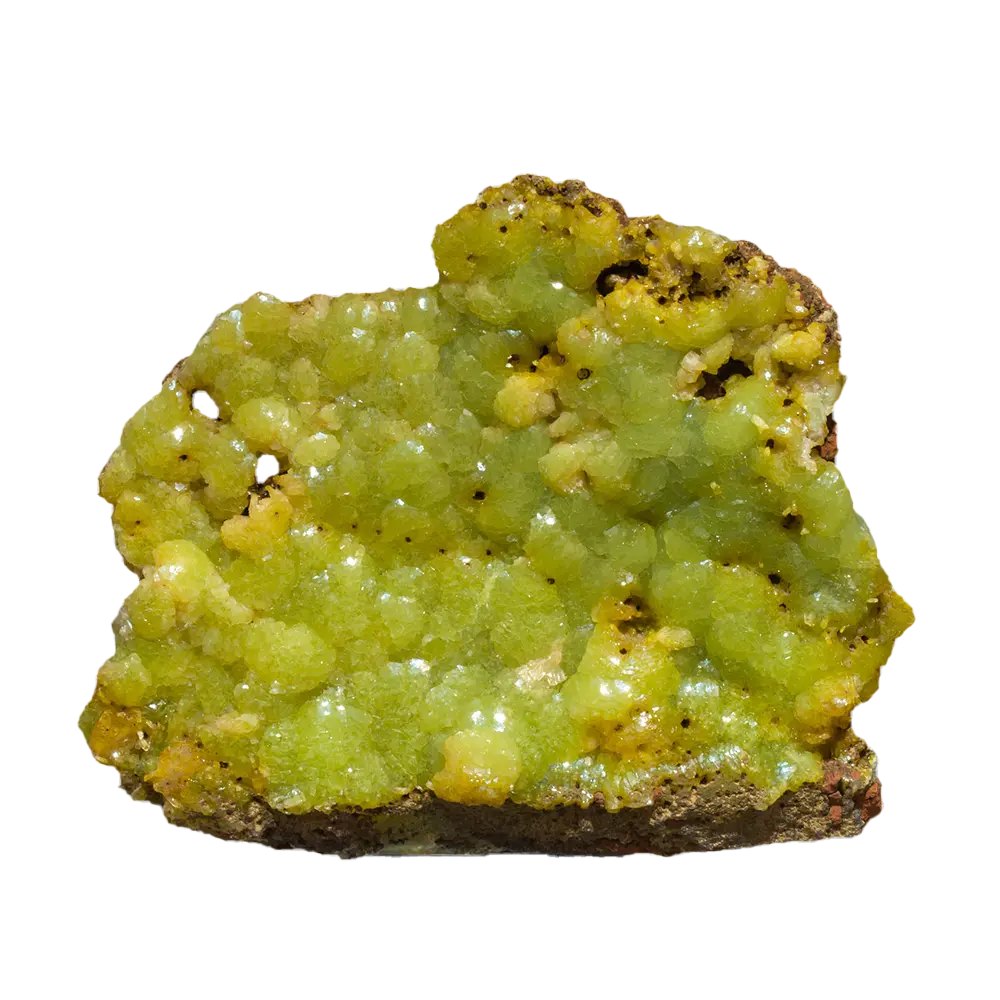

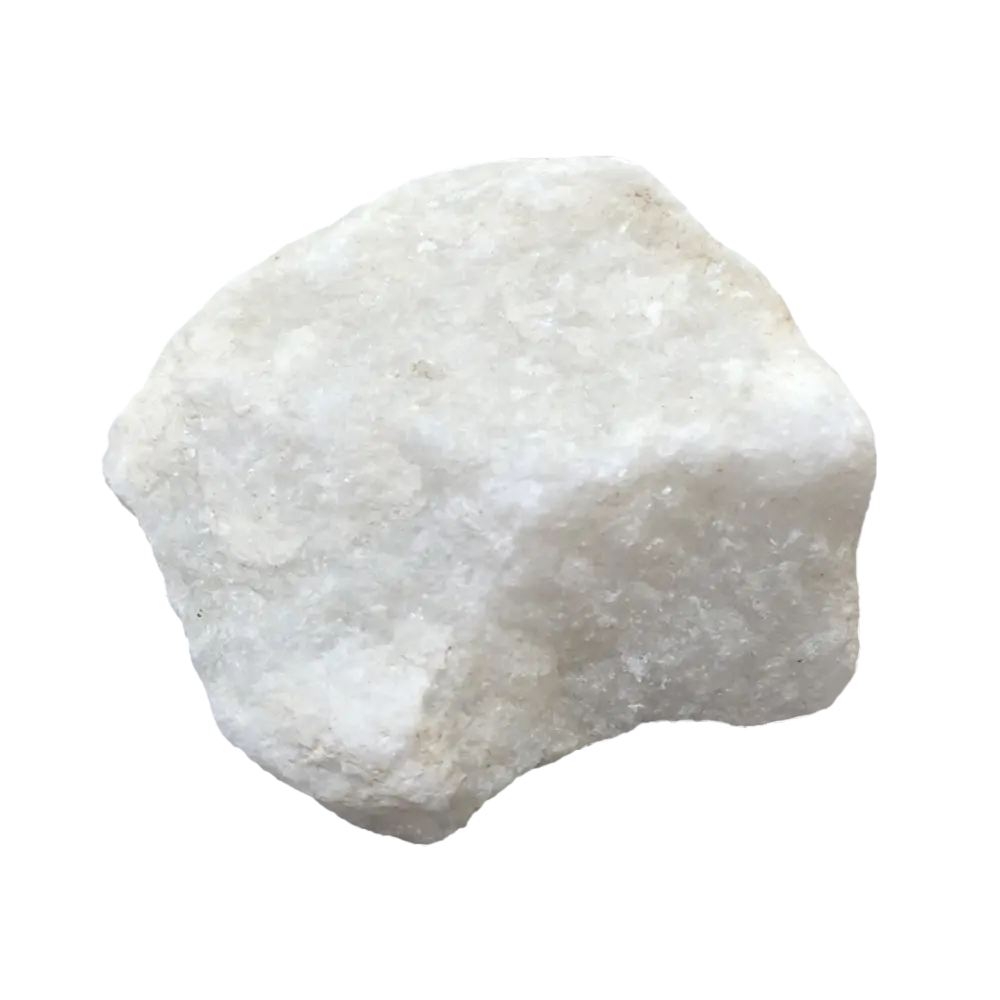

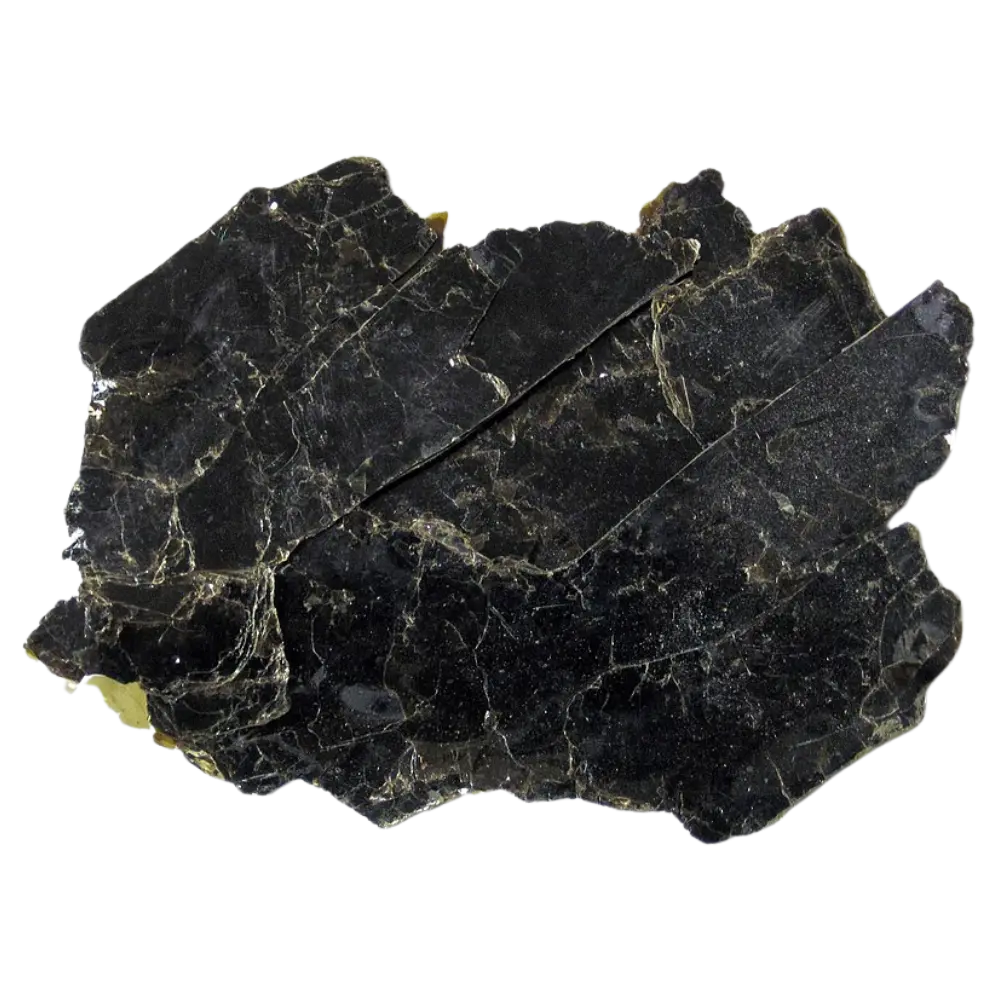

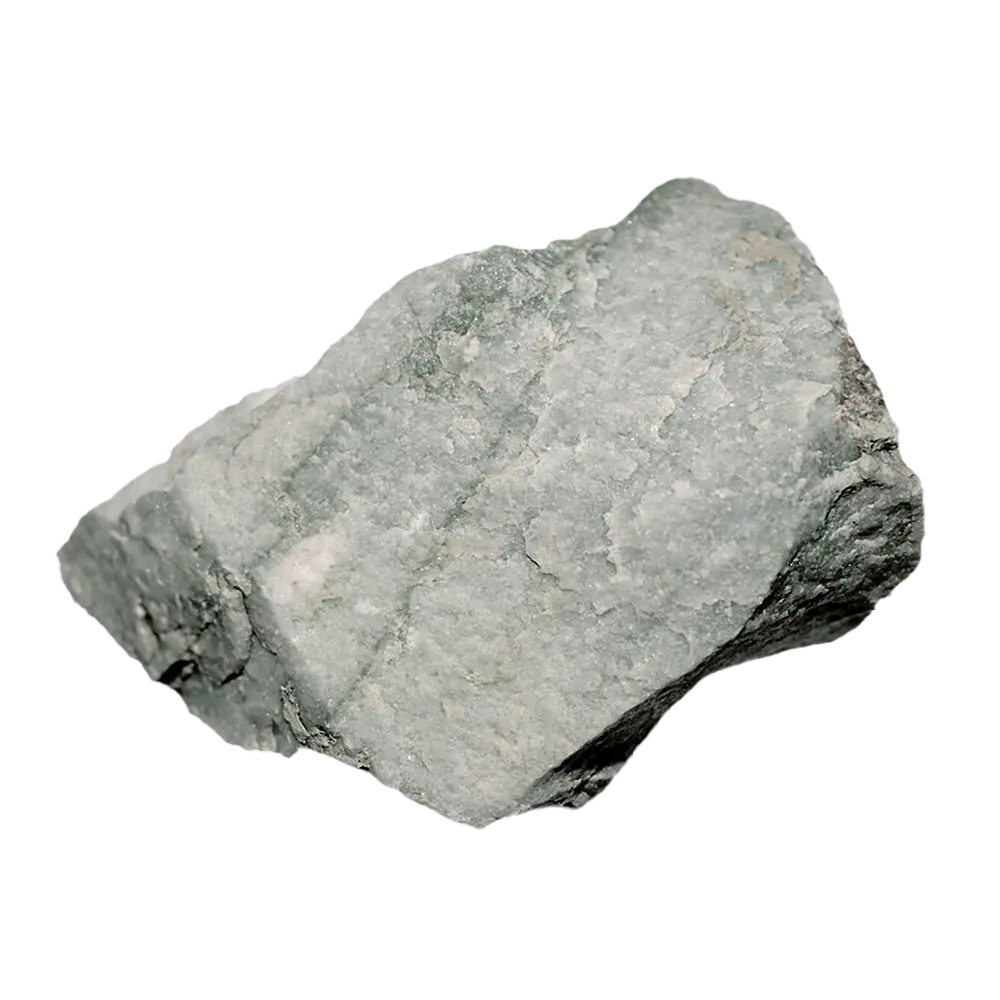

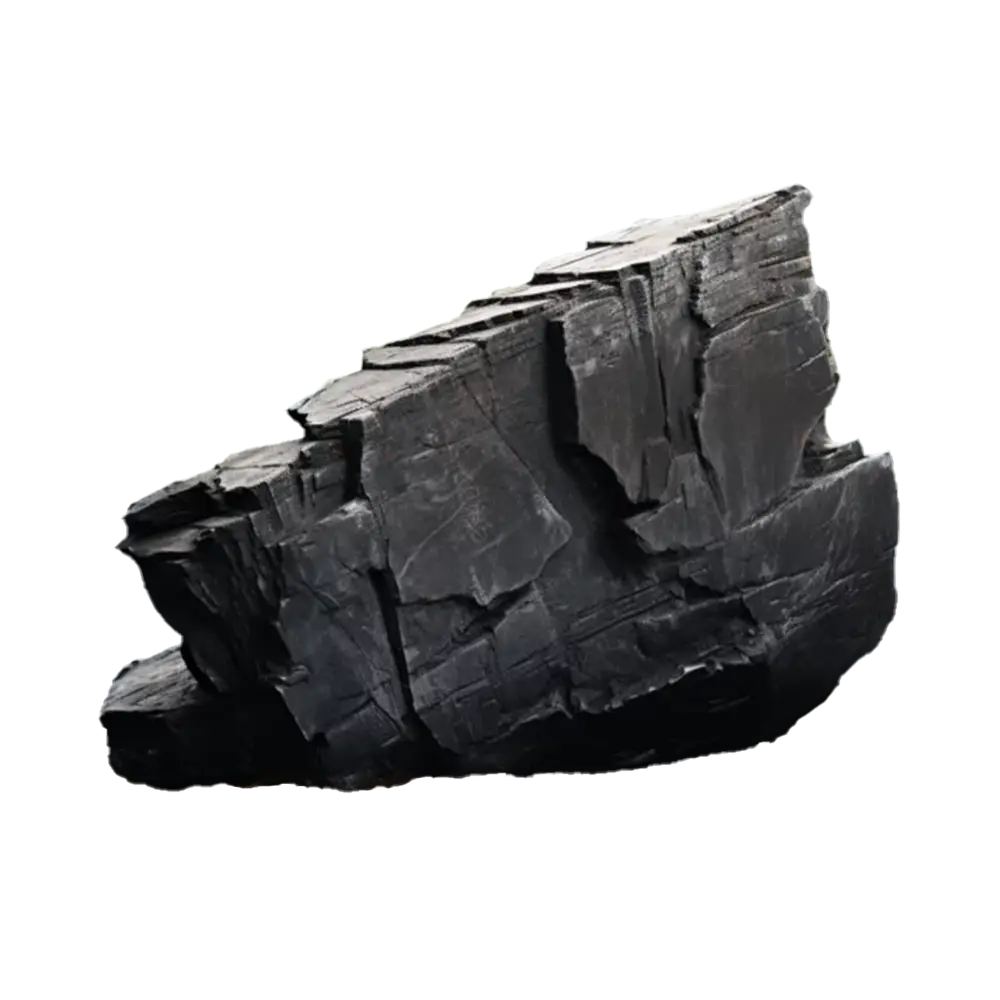

- Hand Lens (Magnifier): A good hand lens (10× magnification is standard) is the geologist’s pocket secret for examining minerals and textures up close[3][4]. With a hand lens, that “gray rock” reveals its sparkly quartz and pink feldspar, or the tiny fossils hidden in limestone. Keep your hand lens on a lanyard around your neck so it’s always handy – you’ll use it constantly.

- Rock Hammer: The iconic geology tool! A rock hammer lets you chip fresh surfaces off a rock to see what’s inside. Choose a quality geological hammer (Estwing is a trusted brand) with a pointed or chisel end for prying and a flat head for striking[5]. IMPORTANT: Always wear safety glasses when hammering rocks[6]. Flying rock chips can cause serious eye injuries, so don’t take chances – even a cheap pair of safety goggles can save your vision. Use your hammer sparingly and only where it’s allowed (some protected sites forbid hammering)[7]. Often, you can find already-broken pieces to examine without excessive whacking.

- Compass and Field Mapping Tools: To do any field mapping techniques, you’ll need a compass with a clinometer. A geologist’s compass (like the Brunton compass) is used to measure the orientation of rock layers and faults – the strike and dip of bedding or foliation[8]. Learning how to do geological mapping means learning to take these measurements accurately and plot them on your map. A clipboard or map board is handy for holding your base map in the field[9], and a ruler or tape measure helps with logging stratigraphic sections or measuring features. Some geologists also carry a Jacob’s staff (a marked rod) to measure thicknesses of rock outcrops[8], though for beginners a tape measure or even pacing out distances can work. In today’s world you might augment your toolkit with a GPS device or smartphone for location data, but it’s good practice to learn old-school map reading and navigation with a compass in case batteries die or signals drop.

- Backcountry Essentials: Fieldwork often means hiking in remote areas, so think like a hiker. Carry a small first aid kit (bandages, antiseptic, any personal medications, pain reliever, blister care)[10]. Bring sunscreen (and reapply it – geologists can get seriously sunburnt spending all day on an outcrop) and insect repellent if bugs are a concern[11]. A flashlight or headlamp is wise if there’s any chance you’ll be out late or exploring caves. A pocket knife or multitool can be very useful for random tasks[2]. And depending on terrain, a pair of hiking poles can save your knees and improve balance on steep slopes (plus you can use them to probe unsafe ground ahead). Don’t forget a whistle – it’s a simple safety device to signal for help if needed[12].

In short, geological fieldwork gear is about balancing preparedness with portability. Everything in your pack should have a purpose. Lay out your gear before the trip and check it twice. As the saying goes, “there’s no such thing as bad weather, only bad gear” – while we hope for sunny skies on field days, you’ll be grateful for that rain jacket when the weather turns or that extra water when the hike runs long.

Field Safety for Geologists: Preparation and Awareness

Fieldwork is exciting, but it isn’t a casual stroll in the park – it’s an outdoor adventure with real risks. In fact, the Geological Society’s code of conduct reminds us that fieldwork is potentially hazardous, and those spectacular cliffs or quarry walls that provide the best rock exposures are also inherently dangerous places[13]. Being safe in the field isn’t about being fearful; it’s about being aware, prepared, and proactive so you can focus on the science (and fun) instead of scrambling out of trouble. Here are some key field safety tips for geologists:

- Plan and Communicate: Never head to a remote field site without telling someone where you’re going and when you plan to return. If possible, don’t work alone in isolated areas[14] – the buddy system can be a literal life-saver if someone gets injured or lost. Obtain any necessary permissions for the land you’ll visit (for example, don’t just waltz into an active quarry or private property without clearance[13]). Before you go, study maps and understand the terrain. Know the location of hazards like cliffs, unstable slopes, or deep water. Check the weather forecast and have a plan for if it turns bad or if darkness falls. In mountain or coastal areas, time your work around natural hazards (e.g. don’t get trapped by the rising tide on a sea cliff[7]!).

- Dress for Safety: We mentioned boots and proper attire already – this is not the time for sandals or shorts. Sturdy, non-slip boots protect you from foot and leg injuries on rocky ground[15]. If you’ll be around any kind of overhanging outcrop or where rocks might fall (e.g. in a quarry or near a cliff face), wear a hard hat[16]. It may feel goofy at first, but it beats a head injury. Gloves are useful when handling sharp rocks or thorny bushes. And always have those safety glasses ready when using your hammer[17] – no “ifs or buts,” as one field guide puts it, eye protection is mandatory when striking rocks.

- On-Site Awareness: Once in the field, constantly be aware of your surroundings. Watch your footing on loose or steep ground to prevent falls. Don’t climb rock faces that look unstable – if you need to examine something high on a cliff, use binoculars or find a safe way around rather than risking a dangerous climb[18]. Be mindful of wildlife: in some regions that could mean snakes underfoot, in others maybe bears or aggressive goats (yes, that happens!). In any environment, stay situationally aware – it’s easy to get so absorbed in examining a fossil or mineral that you don’t notice a wave coming in or a thunderstorm rolling up. Take a moment now and then to look up, look around, and ensure you’re safe.

- Stay Hydrated and Healthy: Geology field days can be long and physically taxing. Carry more water than you think you need (dehydration sneaks up on you, especially in hot, arid regions). Take breaks in the shade when you can to avoid heat exhaustion. Use sunscreen liberally – geologists have a saying that “sunscreen and a rock hammer go hand-in-hand.” Also, eat snacks throughout the day to keep your energy up; fieldwork can burn a lot of calories. If you’re in high elevations, pace yourself to avoid altitude sickness. And know your limits – pushing too hard when you’re exhausted can lead to mistakes or accidents, so it’s okay to call it a day when fatigue sets in.

- Emergency Prep: In your pack, keep that first aid kit and perhaps an emergency bivy or space blanket, especially if there’s any chance of being out overnight unexpectedly. A charged phone (with a portable battery) can be a lifeline, but in very remote areas consider carrying a satellite communicator or personal locator beacon for true emergencies. Know basic first aid or travel with someone who does. If an accident happens, having a whistle (three blasts is an emergency signal) or a mirror to signal can help searchers find you. It’s also good practice to note the nearest hospital location or have emergency numbers (like park rangers) on hand for the area you’re in.

Field safety for geologists comes down to common sense and preparation. As much as we cherish fieldwork, we must respect the power of nature and the unforgiving side of the outdoors. By planning ahead and following these safety guidelines, you can mitigate most risks. That leaves you free to fully enjoy the adventure of geological fieldwork with peace of mind.

Field Mapping Techniques: How to Do Geological Mapping

At the heart of many geology field trips is the creation of a geologic map – basically a picture (on paper or digital) of the distribution of rocks and structures in the area you’re studying. Doing geological mapping is like solving a puzzle: you gather clues from outcrops and put them together to understand the big picture of the area’s geologic history. So, how do you actually do geological mapping in the field? Let’s break down the basic techniques.

Mapping starts before you even set foot outside. You’ll want a base map of the area – often a topographic map or aerial imagery – that you can draw on. Nowadays you might use a GPS-enabled tablet, but it’s wise to carry a paper topo map and a compass as backup. Study any existing geologic maps or reports of the region if available, so you have an idea what rock units and structures to expect. This background research can guide your planning (though be ready for surprises!).

Once in the field, you move from one exposure (outcrop) to another, making observations at each station. At every stop, note where you are (mark it on your map, record GPS coordinates, or use landmarks), what rock types you see, and any structures (like bedding planes, faults, folds, veins) present. Good field notes are detailed but concise – include descriptions of color, grain size, mineral content, fossils, hardness, weathering, etc., for each rock unit. Sketch what you see: a quick outcrop sketch or a cross-section in your notebook can capture orientations and relationships better than words alone. Remember, fieldwork is an opportunity to practice a variety of techniques that will serve you later: taking effective notes, making sketches and maps by hand, and even snapping photos of key features to jog your memory back home[19].

One of the key field mapping techniques is measuring the attitude of rock layers – their strike and dip. Using your compass clinometer (e.g. a Brunton compass), line it up on a bedding plane or foliation surface to record the strike (the compass direction of the line of intersection of the plane with horizontal) and the dip (the angle the plane makes with horizontal, measured down from the strike direction). It sounds technical, but with practice it becomes second nature. These measurements let you draw those little T symbols or dip ticks on your map, which indicate how layers are tilted. They are crucial for interpreting the geologic structure of the area[8]. Similarly, you might measure the trend and plunge of lineations or orientations of fractures – all data that go into your map and later analysis.

As you hike around, you’ll be continually updating your geologic map. When you find the boundary between two rock types (a contact), you trace it on your base map as accurately as possible – sometimes it’s exposed, other times you infer its position under soil or vegetation. You use clues like float (loose rocks), changes in slope or soil, or vegetation differences to guess where the contact goes when it’s not visible. Every time you hit an outcrop, you try to identify which map unit it belongs to (or define a new unit) and mark that on the map. Over time, a picture emerges of which rock formations are where. Field mapping is detective work: you formulate hypotheses (“maybe this sandstone layer continues over that ridge”) and then hike out to check. You will refine your map with each observation.

Traditional mapping is done with notebook, compass, and map, but modern geologists also leverage technology. You might use a GPS device to record precise locations of observations, or mobile apps like StraboSpot or ArcGIS Field Maps to draw contacts digitally in the field. Drones (UAVs) have even become useful to get aerial images of inaccessible outcrops[20]. Still, it’s important to learn the fundamentals by hand first – technology can speed things up, but you need a geologist’s eye to interpret the landscape. Many field courses teach a mix of classic and modern methods: for instance, mapping on paper in the field, then later scanning or digitizing your map using GIS software[19]. This way you get the best of both worlds. As you gain experience, you’ll figure out what combination of tools works best for you.

By the end of your fieldwork, you’ll compile all your measurements, notes, and sketches to produce a finished geologic map and perhaps cross-sections or a report. This process teaches you how to synthesize data and tell a geological story of the area – e.g., “Unit A lies on top of Unit B along an angular unconformity, and both are cut by a fault trending NE-SW,” and so on. The ultimate goal is to create a coherent interpretation: how these rocks got where they are, in what sequence, and what it implies about the region’s geologic history. It’s incredibly rewarding to stand back and realize that the map you’ve drawn was hidden in plain sight in the rocks around you, and through careful work, you’ve made sense of it.

For beginners, geological mapping can feel overwhelming at first – there’s a lot to observe! But stick with it. Start with broad distinctions (e.g., “this is granite, that’s sandstone over there”) and gradually work out the details. Ask your peers or mentors if you’re unsure about an observation. And remember that making mistakes is part of the learning process. Even seasoned geologists find surprises in the field that require them to rethink their maps. Stay curious and keep honing your observation skills. With time, you’ll start to “read” the rocks and landforms with the trained eyes of a geoscientist, and that’s a superpower that only comes from field experience.

Geology Field Tips and Global Insights

No two fieldwork experiences are the same – and that’s part of the magic. Geology is a global science, and field practices can vary from mapping an alpine valley in Switzerland to logging a drill core in the Australian Outback. But some tips are universal to good fieldwork. Here are a few geology field tips and insights gathered from professionals around the world:

Embrace the Adventure (But Be Adaptable): Field geology often takes you off the beaten path – literally. You might find yourself traveling to remote and stunning places, which many geologists cite as one of the greatest perks of the profession[21]. One week you could be trekking through tropical jungles to examine an outcrop, another week wading in a river to measure sediment layers, or camping under desert stars near rock formations. Embrace these opportunities – they’re not just work, but life experiences. That said, always be adaptable. Plans can change due to weather, access issues, or “interesting” logistical hurdles (missed bush planes, anyone?). The outcrop you needed to see might be flooded or a road might be closed. Veteran field geologists will tell you: have a Plan B (and C). Flexibility and a good humor will save the day when things inevitably don’t go as planned.

Respect Local Knowledge and Culture: If you work in an unfamiliar region or country, take time to learn about the local context. Often, local residents, park rangers, or landowners have valuable information – they might know where certain rocks are exposed, which roads are passable, or where not to go (due to sacred sites or hazards). Always ask permission when accessing private lands[22] and respect any guidelines provided. Try to learn a few phrases of the local language if it’s different from yours; it goes a long way in building trust. And be a good ambassador of science: friendly curiosity and gratitude can turn a chance meeting with a farmer or hiker into an enlightening exchange (they might point you to an amazing fossil bed, or you might explain what that weird-looking instrument you’re carrying does!).

Document Everything: In the digital age, don’t shy away from using your phone or camera (where allowed) to document outcrops, formations, and your field days. Take lots of photos of rock features, but also broader context shots. These are not only useful for later analysis, but also for sharing your work with colleagues or on social media to excite the public about geology. Some geologists even keep a field vlog or daily journal. It’s fun to look back on, and it helps build science communication skills. When you take photos, note the scale (include your hammer or a notebook for scale) and location so you can match them with your notes later. There’s nothing worse than finding an excellent structure in a photo but later not remembering exactly where it was or what direction the view is.

Little Tricks of the Trade: Seasoned geos develop all sorts of handy tricks. For example, carry a brunton compass mirror or a separate small mirror – it can help you see underside of an outcrop or reflect light on a dark rock face. Have a couple of Ziploc bags; they’re great for both storing samples and keeping your field notes dry if it pours. A bandana can serve as sun protection, a sweat rag, or even a makeshift bandage. Flagging tape or chalk can mark a spot or orientation line on a rock while you measure or photograph it. If you’re doing a lot of hiking on loose scree, gaiters (covers for your boots) will keep annoying pebbles out of your shoes. And here’s a tip for those in areas with leeches or mosquitoes: a little bottle of salt or a lighter – each handles the pests in its own way!

Global Awareness: Field geology also teaches you about the environment and human impact. As you travel for geology, you might witness climate change effects first-hand (like receding glaciers or bleached coral). You may see environmental challenges like mines or quarries that need careful management. These experiences can deepen your understanding of why sustainable practices and geo-conservation are important. Many countries now have geotourism initiatives and protected geoparks – visiting those can be inspiring and offer insight into how geological heritage is valued around the world. So, keep an open mind and observe not just the rocks, but how geology intersects with ecosystems and communities globally.

Network and Learn from Others: If you get a chance to attend field workshops or trips with experienced geologists (maybe through a university, a geological survey, or a local rockhound club), go for it. Working alongside others is one of the best ways to pick up field techniques and tips. It also makes field days more enjoyable – swapping stories and interpretations with fellow geo-nerds is incredibly enriching. As the Association of Environmental & Engineering Geologists notes, fieldwork often involves teamwork and bonding with fellow students and colleagues, which leads to great connections and often better scientific results than working solo[23]. Plus, an extra set of eyes might spot something you missed. Geology is collaborative by nature; in the field, you’ll quickly learn that two heads are better than one when puzzling over a perplexing outcrop.

Finally, remember that field geology is as much art as science. Every geologist develops their own style in the field – from how they jot notes to how they pace out a section. You’ll develop yours too. Stay curious, keep a sense of wonder, and don’t be afraid to ask questions. The best geologists are always learning. When you approach fieldwork with a beginner’s mind, even if you’re experienced, you remain open to new discoveries. And sometimes, those unexpected discoveries – stumbling on an unmarked fossil site, or noticing a weird pattern in the rocks – become the most memorable part of your field experience.

Beyond the Rocks: How Fieldwork Shapes a Geoscientist

Spend enough time doing field geology, and you’ll find it’s not just about rocks – it’s about personal growth and gaining a new perspective on the world. Fieldwork has a way of teaching life lessons and professional skills in a manner unlike any classroom or office. Here are some philosophical insights on what fieldwork teaches and how it shapes geoscientists:

- “The best geologist is the one who has seen the most rocks.” This famous quote by Herbert Harold Read (often recited by geology mentors) encapsulates the value of exposure and experience. In geology, book knowledge is important, but there is no substitute for real field experience[24]. Each new outcrop you examine, each terrain you traverse, adds to your mental library of geological examples. Patterns start to emerge in your mind – you recognize a sedimentary structure or a mineral you’ve seen before, and that helps you interpret new sites more quickly. In essence, fieldwork builds your geologic intuition. You begin to “think in 3D (and 4D with time)”, visualizing structures beneath your feet and how they evolved[25][26]. This spatial thinking and deep time perspective are unique to geoscientists, and they develop only with practice and observation. So, if you want to grow as a geologist, get out there and see as many rocks as you can – the world is the best classroom.

- Sharpening the Scientific Mind: Fieldwork is the arena where you learn to formulate and test hypotheses on the fly. You see something unexpected and you ask, “Huh, what’s going on here?” Then you gather evidence around it to answer that. In the field, you often have to make decisions with incomplete data – do I interpret this structure as a fault or just a weird bedding plane? – and it teaches you to live with a degree of uncertainty while you seek more clues. You develop critical thinking and resilience in problem-solving. As one field geologist noted, everything comes together in the field and forces attendees to think out of the box and rely heavily on multiple working hypotheses to resolve problems[27]. In other words, you get comfortable with not having immediate answers and instead craft several possible explanations that you’ll test as you gather more data. This mental flexibility and scientific rigor is a hallmark of a trained geoscientist.

- Patience, Perseverance, and Grit: Fieldwork can be tough. You might be hiking for hours, roasting under a desert sun or shivering on a windswept ridge, and not immediately finding what you’re looking for. It teaches you patience. Geology doesn’t always reveal its secrets easily – you might spend days mapping before the puzzle pieces click. The perseverance you develop (“I will climb one more hill to see if the formation is exposed there”) often pays off in discoveries. Facing and overcoming physical and mental challenges in the field also builds confidence and grit. After you’ve navigated by map and compass through a whiteout blizzard or fixed a flat tire on a remote dirt road, other challenges in life might seem a bit more manageable. Fieldwork instills a quiet confidence: you learn that you can handle uncertainty and discomfort, and still get the job done.

- Teamwork and Leadership: As mentioned, field geology is often a team endeavor. Working with a partner or a crew in unfamiliar environments teaches you to trust others and communicate clearly. You learn to divide tasks, share observations, and double-check each other’s interpretations. If you eventually lead field expeditions or student trips, you also learn leadership – how to plan logistics, keep people safe, and maintain morale (pro tip: always pack some extra snacks to share; hungry field partners are unhappy field partners!). The camaraderie built during fieldwork can be special – there’s nothing like swapping stories around a campfire after a hard day’s work or collectively marveling at a beautiful view from a outcrop you all struggled to reach. These social bonds and networks can last a lifetime and significantly shape your professional journey. Many a career opportunity or collaboration has sprouted from friendships forged on a field trip.

- Perspective and Humility: Perhaps one of the most profound impacts of field geology is how it shifts your perspective. When you stand on an ancient rock that’s a billion years old, or map layers that record long-lost environments, you can’t help but feel a sense of awe. Fieldwork connects you to the enormity of geologic time and the complexity of Earth systems. It’s humbling – humans are tiny blips in Earth’s story. This can instill a deep respect for nature and a desire to communicate its wonders. Many geologists become passionate advocates for science communication or conservation because of what they’ve seen in the field. As geologist Bill Elliott eloquently put it, “Geology is in the field, not in the laboratory or classroom… The more rocks we see in the field, the more we recognize similarities and differences… Now slip on your field boots, grab your Brunton, rock hammer, Jacob’s staff, pencil and paper and go out there, be one with nature, and do the best job you can.”[26][28] This sentiment underscores how fieldwork not only builds knowledge but also character and a sense of mission. You come back from the field not quite the same person – often tired, often dirty, but invariably inspired (and already planning the next trip!).

Geological fieldwork shapes you into a sharper scientist and a more well-rounded human being. It teaches you to observe closely, think critically, work collaboratively, and appreciate the planet in a way few people do. These lessons stay with you, whether you’re analyzing samples in the lab, writing reports, or even in everyday life when you notice the landscape around you with new eyes.

Conclusion

Field geology is both practical and poetic. It’s about tips and tools – making sure you packed your compass, your map, your lunch, and your sunscreen – and it’s about intangibles like curiosity, courage, and the willingness to get a little lost (mentally or physically) to find something new. As you venture out on geological fieldwork, remember that you’re part of a grand tradition of geoscientists, from pioneering explorers mapping uncharted territories to modern students fanning out on their first field trips. Each outcrop you visit, each sample you collect, each map you draw is a contribution to understanding our Earth – and a new story you’ll have to tell.

So, field geology 101 distilled: prepare well, stay safe, observe deeply, and learn from everything. Pack your gear, do your homework on where you’re going, respect the land and people, and then dive in with an open mind. Take those time-tested geology field tips with you: drink water, take good notes, wear your darn safety glasses when you hammer, heed the weather, and listen to your instincts. Balance diligence with delight – yes, you might be on a mission to log that section or find that boundary, but don’t forget to pause and appreciate the beauty of your surroundings and the deep history written in the rocks.

Lastly, keep the passion alive. Fieldwork can be challenging, but it’s also fun. The best geologists are often the ones who still approach the outcrop with childlike excitement, even after decades. If you ever find yourself weary, just imagine the likes of James Hutton or Mary Anning in the field, scratching their heads over a puzzling formation but utterly absorbed by the puzzle. The spirit of discovery is why we do this.

Now it’s your turn: slip on your field boots, grab your map and hammer, and go make some geologic memories. The world’s out there, ready to share its deep secrets with those willing to look. Field geology will test you and teach you, but it will also reward you with stories and insights impossible to gain any other way. Embrace the journey – and happy fieldworking! You’ve got this. 🚩 🪨🌎

Sources:

- UC Davis Earth & Planetary Sciences – Fieldwork Gear Checklist (essential field gear for geology students)[1][2].

- GEOetc – Field Essentials (recommended tools like hand lens, field notebook, rock hammer, safety glasses)[3][17].

- Geological Society Code for Geological Fieldwork – safety guidelines for field conduct (hazards, permissions, protective gear, etc.)[13][7].

- Association of Environmental & Engineering Geologists (AEG) – Benefits of Field Work (on the value of field experience, tools usage, and teamwork in the field)[21][23].

- AEG – How Important is Field Work… by Amy Ashworth (practical skills gained through fieldwork: note-taking, mapping, reporting)[19].

- Comments by professional geologists on fieldwork (AEG blog) – insights on field learning and famous quote by H. H. Read (“The best geologist is the one who has seen the most rocks.”)[26][27].