When a living creature turns into a fossil, it’s a tag-team effort between the geology and biology. In essence, fossils are the preserved remnants or evidence of extinct life that has been buried in sediment and is typically older than 10,000 years. Only harder parts, such as bones, shells, or teeth, typically survive long enough to become fossilized after death, with soft tissues rotting away quickly [2]. However, it takes the proper environmental conditions to intervene at the appropriate moment in order to turn bone into stone. Actually, paleontologists identify two key elements that determine whether an organism disappears or turns into a fossil[3].:

- The environment of burial: Where and how quickly the organism gets buried in sediment.

- The composition of the organism’s body: What materials the organism was made of (soft tissue vs. hard parts like mineralized bone or shell).

Biology’s Role: Hard Parts and Decay Resistance

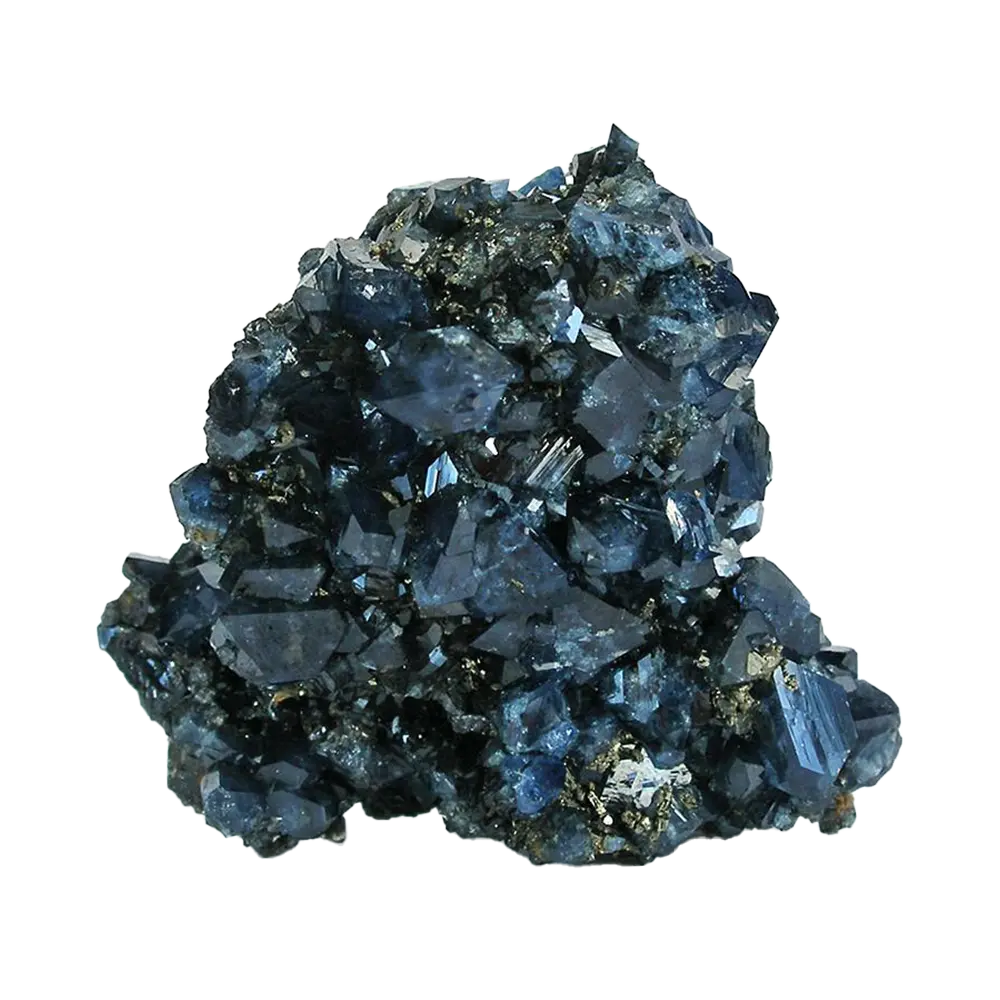

When it comes to fossilization, some body parts just have better odds than others. Creatures with hard parts—think shells made of calcite or aragonite, or bones packed with calcium phosphate—start off with a serious leg up [4]. These tough tissues are already built from minerals, so they don’t fall apart as quickly as soft tissues do [5]. In other words, a clamshell or a dinosaur bone has a decent chance of “holding out” until it gets buried, whereas an animal’s internal organs or an insect’s delicate exoskeleton usually decompose long before they can be preserved. It’s no surprise, then, that the fossil record is dominated by the mineralized hard parts of organisms[5]. Museum fossil halls are filled with bones and shells, reflecting a bias in what nature tends to preserve.

Figure: A fossil fish from the Eocene Green River Formation shows a larger fish that died while swallowing a smaller fish. The skeletons are exquisitely preserved, yet no soft tissue survived the fossilization process[6]. Hard, mineralized parts like bone can endure long enough to become fossilized, whereas soft flesh is usually lost.

The flip side is that the majority of living species (and likely past species) have no mineralized hard parts at all. For example, insects are incredibly diverse today, but because their bodies lack bones or shells, they very rarely leave fossils compared to shelled creatures like clams or snails[7]. Even having hard parts isn’t a guarantee – it also matters where an organism dies. A dinosaur had sturdy bones, but if it died in a dry upland or a rocky area with no sediment to cover it, those bones could be scattered or destroyed before ever being buried. In fact, many large land animals like dinosaurs are known only from fragmentary remains, because they didn’t live in places where sediment was likely to quickly entomb their carcasses[8][9]. Burying a multi-ton dinosaur in sediment takes a rare catastrophe (imagine the amount of mud needed to cover a 130-foot-long Titanosaur!), whereas burying a small seashell can happen with just a routine wave or river current[9]. Thus, biology provides the “raw materials” (the hard parts to preserve), but without a favorable setting those materials won’t make it into the geological record.

Geology’s Role: Burial and Preservation Processes

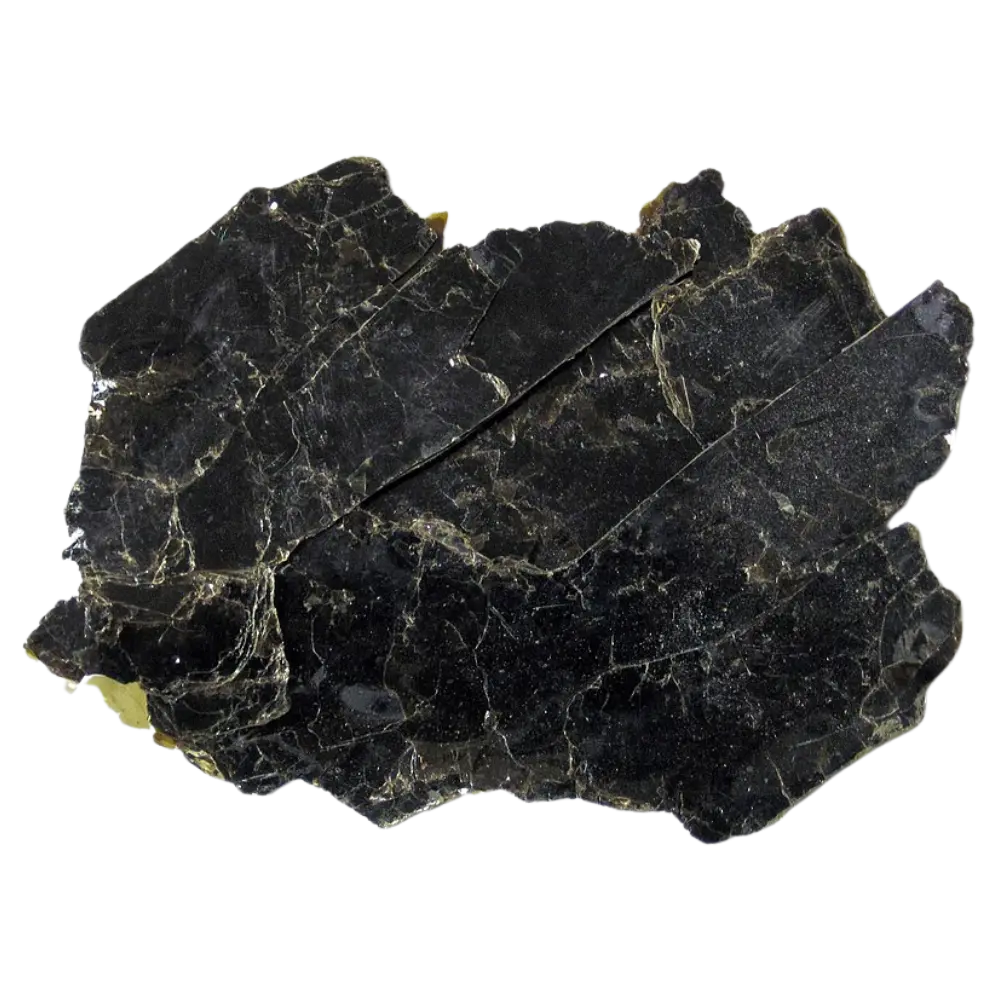

Geology takes over once an organism dies by providing the conditions to preserve it. The most crucial step is rapid burial. If a creature’s remains are quickly covered by sediment (mud, sand, volcanic ash – anything that blankets the organism), they are shielded from the destructive forces of the living world[10]. Burial cuts the remains off from oxygen, scavengers, and bacteria, slowing or halting the decay that would otherwise break them down[10]. That’s why fossils are typically found in depositional environments, places where sediments naturally accumulate. Examples are river deltas, lake beds, floodplains, or ocean floors[11]. Organisms that live in or near these sediment-rich settings (or get washed into them after death) have a much higher chance of fossilization than those living in, say, a mountain top or desert where burial is infrequent[12]. For example, marine clams that die on a muddy seafloor might be buried within days or weeks by the next pulse of sediment, whereas an animal that dies on an exposed plain might lie out in the open for years – plenty of time to be picked apart or dissolved away.

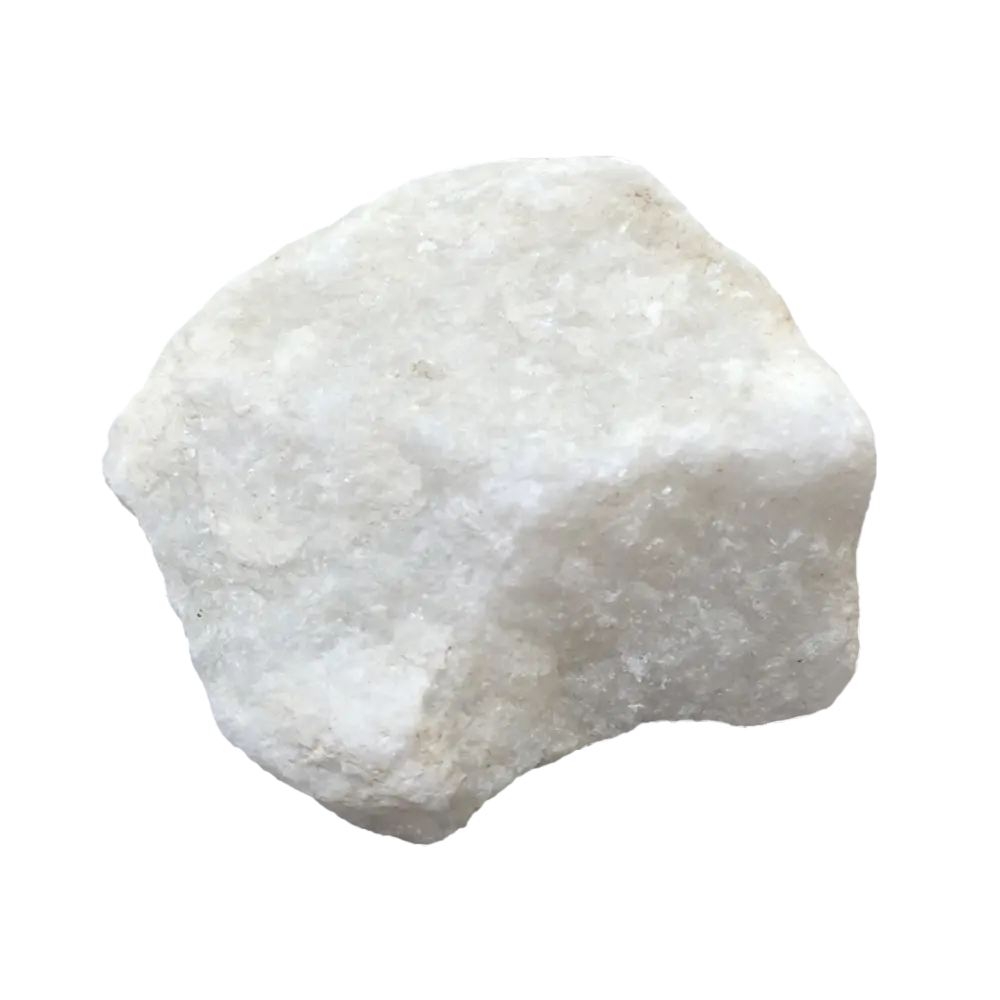

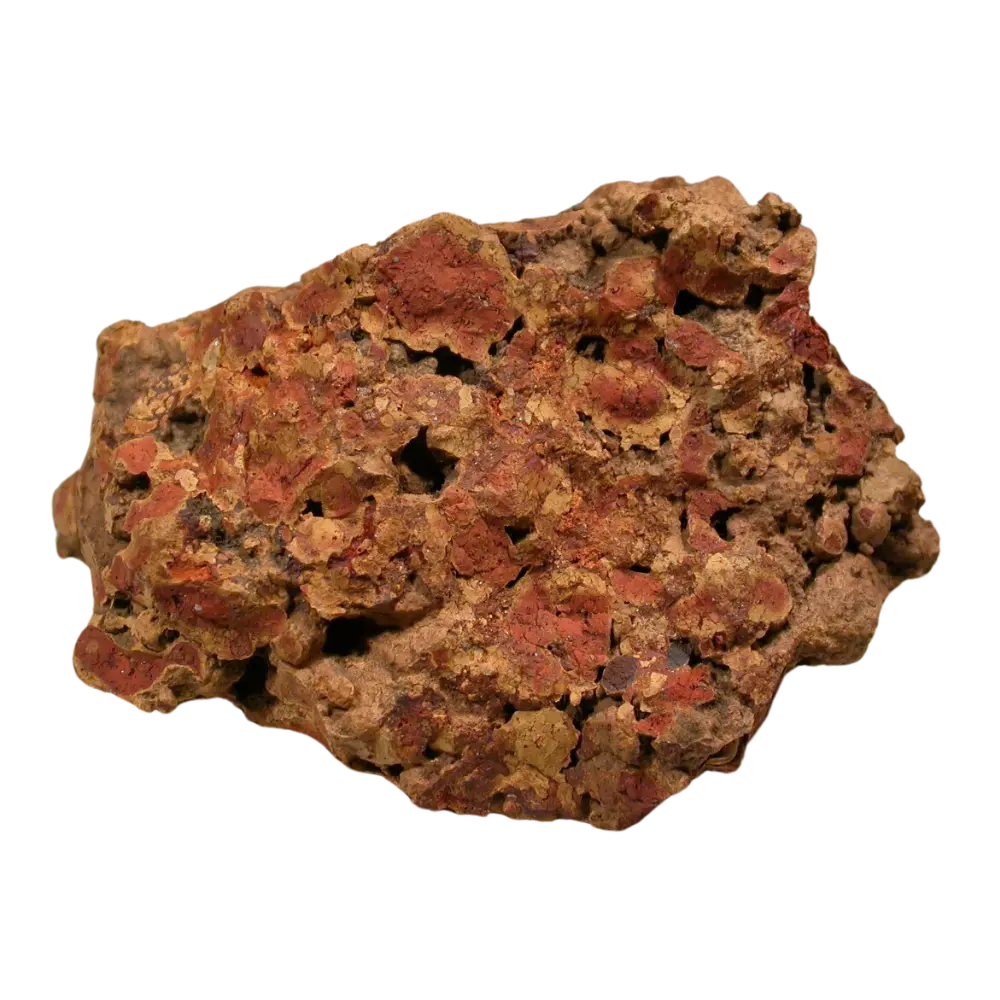

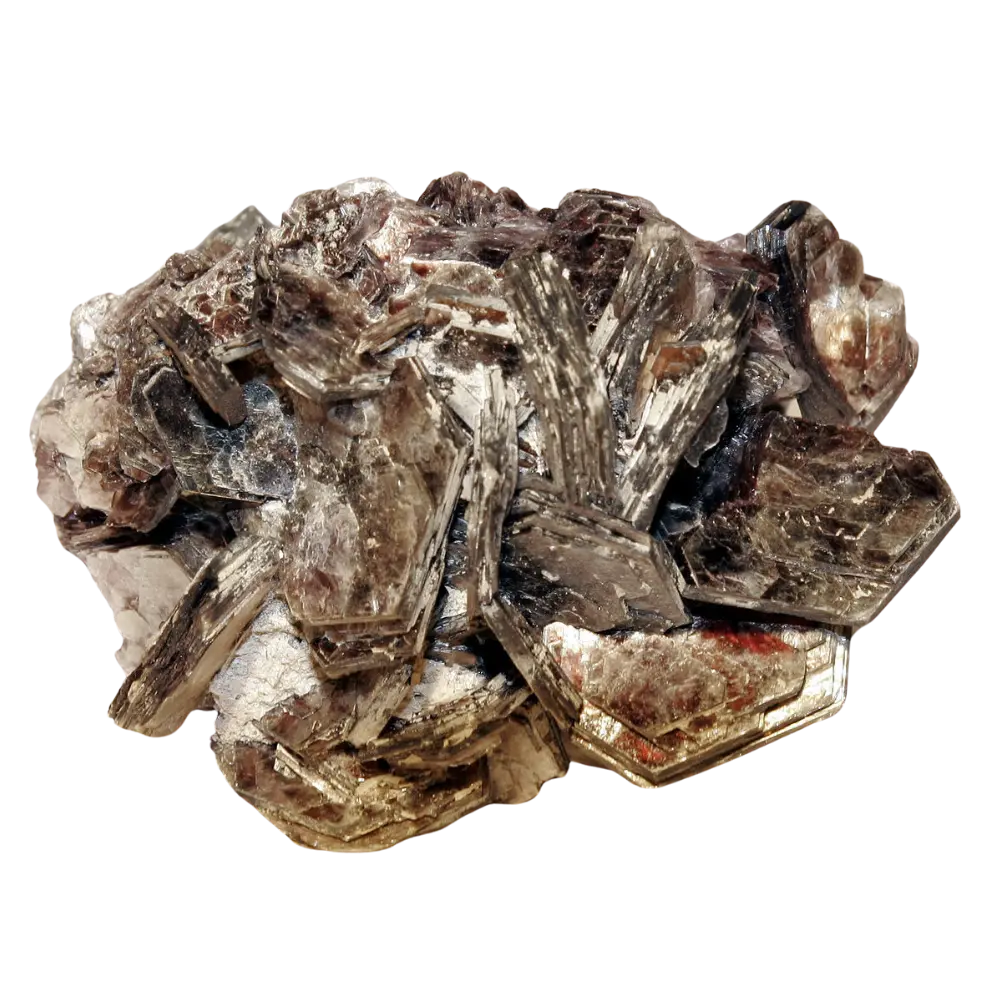

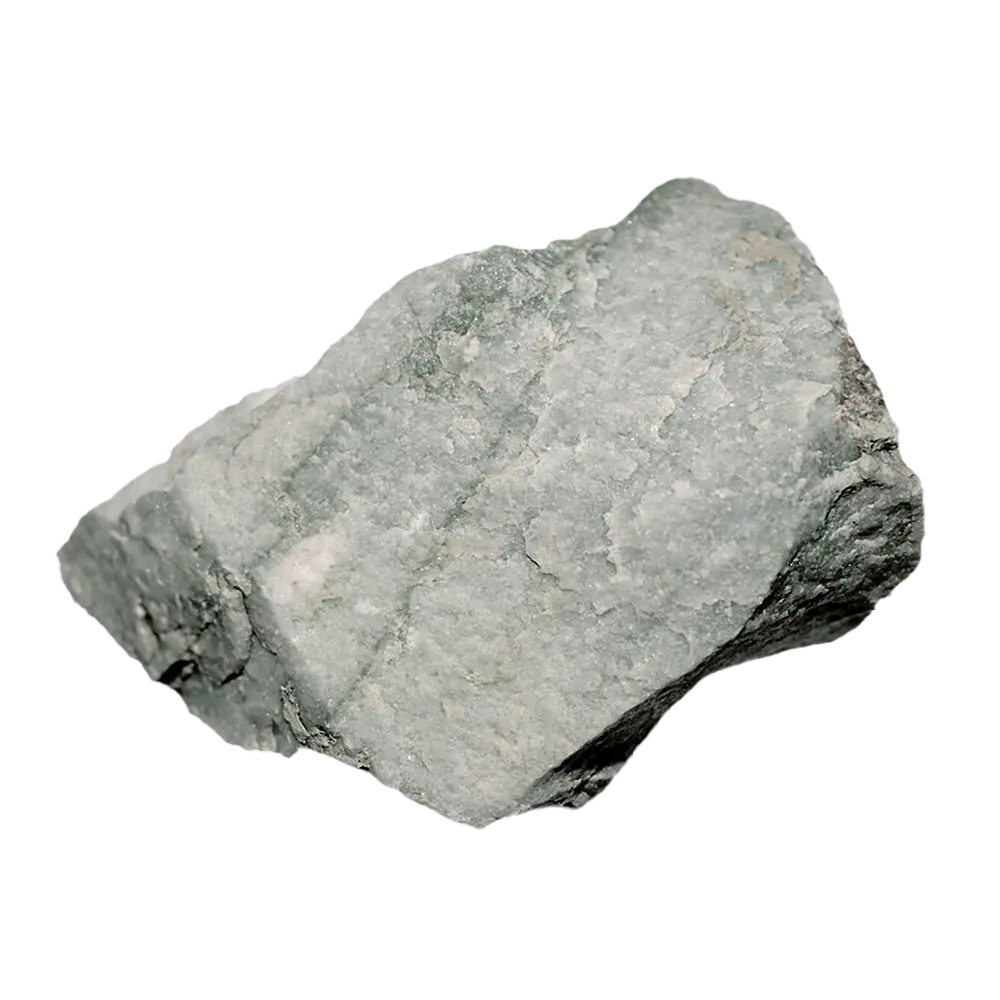

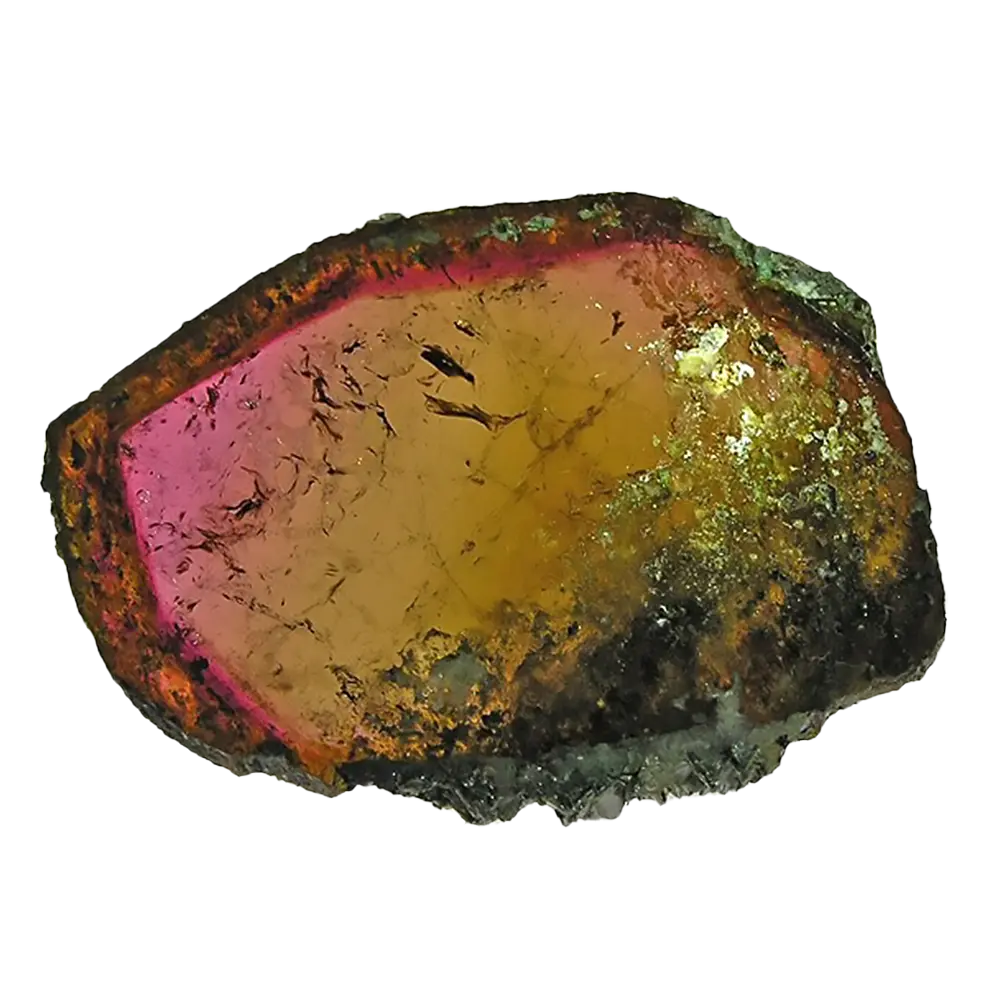

Burial is only the beginning. Once entombed, geochemical processes begin turning the biological remains into rock. Mineral-rich groundwater percolating through the sediment can infiltrate bones, teeth, or wood and deposit minerals in their pores. Over time, this process (called permineralization) are able to completely replace the original organic matter with stone, turning the remains into rock[13]. Common preserving minerals include calcium carbonate or silica, which can fill every tiny space in a bone or piece of wood until it’s fully “petrified”[13]. This is how we get petrified wood and fossil bones that, while retaining the shape and microscopic structure of the original organism, are chemically more like a mineral specimen. In short, geology provides the mineral cement that lithifies the remnants of life.

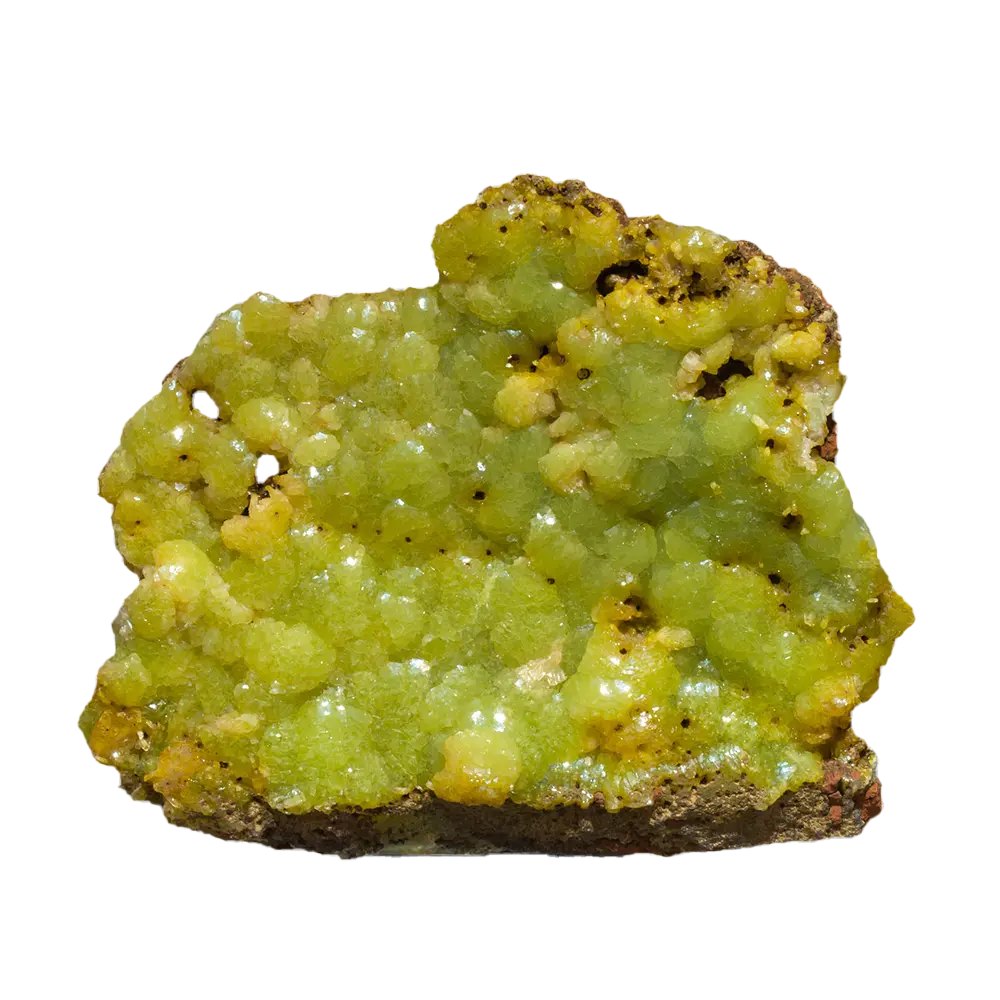

Interestingly, the chemical makeup of the sediment can also influence fossilization in more subtle ways – even determining whether soft tissues get a chance to fossilize. Certain clays, for instance, have antibacterial properties that can slow down decay. Experiments have shown that when animal carcasses (like shrimp in a lab setting) decay in a clay such as kaolinite, the usual decay bacteria don’t thrive as well. After two months, shrimp buried in kaolinite were still in early stages of decomposition with many body parts intact, whereas shrimp on other types of sediment (like different clays without that effect) had decomposed into mere fragments[14]. By suppressing the bacterial communities that normally break down the carcass, the kaolinite clay effectively “buys time” for the remains, keeping them intact longer[15]. Extra time can allow more of the body to undergo mineralization before it’s lost. This example highlights a remarkable interplay between geology and biology: a mineral in the sediment influences the activity of microbes (biology) which in turn affects what gets preserved. In the fossil record, we see hints of this interplay in the exceptional preservation of soft-bodied fossils in certain rock formations where fine clays, rapid burial, and low oxygen combined to limit decay.

Rare Fossils: When Soft Parts Survive

Because preserving soft tissues is so difficult, fossils that show soft anatomy – like skin, feathers, or internal organs – are exceedingly rare and often spectacular. They occur only when the biological remains are locked down by extraordinary geological circumstances. For instance, in very exceptional cases delicate things like feathers or leaves have been fossilized, but usually only when decay was halted almost immediately[2]. Some famous Lagerstätten (“storage places” of exceptional fossils) like the mid-Cambrian Burgess Shale formed when animals were swept into anoxic (oxygen-poor) environments and rapidly buried by fine mud. With little oxygen and perhaps the presence of certain clays or sulfides, decay bacteria didn’t get far, and even soft-bodied critters left imprints or carbon films of their bodies. In other cases, nature entombed organisms in substances that bypass decay entirely – consider insects trapped in amber (hardened tree resin). These unlucky bugs are preserved virtually whole, often down to their fragile wings and eyeballs, because the sticky resin encased them and hardened into a polymer tomb before decomposition could set in[16]. Freezing can have a similar effect: the bodies of Ice Age mammoths have been found in permafrost with hair and flesh intact after tens of thousands of years, essentially because they stayed frozen from death until discovery. All these scenarios require a perfect convergence of biology and geology – the organism’s remains must meet exactly the right entombing agent or conditions at just the right moment.

Fossil formation is a conversation between life and Earth. The organism provides the parts worth preserving, and the Earth provides the shelter and minerals to preserve them. Without the organism’s biological hard parts and the geological capers of burial and mineralization, we would have no fossils at all – no petrified wood, no dinosaur bones, no shells turned to stone[3][13]. Every fossil is a tiny miracle of cooperation between biology and geology, recording a moment when the living world and the earth itself worked hand-in-hand to defy decay and capture a fragment of ancient life for perpetuity. Each time we pick up a fossil, we’re holding the result of this interplay: life’s story written in rock.