Introduction: A Tongue-in-Cheek Tradition in Geology

Yes, geologists really do lick rocks. If you’ve ever caught a field geologist sneaking a lick of a stone, you might wonder if the wilderness made them a bit crazy (or hungry!). But fear not, this quirky practice isn’t about geologists snacking on the scenery. In fact, it’s a time-honored, scientifically useful trick in geology field identification. This guide will dive into why geologists lick rocks (the method behind the madness, essentially “rock licking explained”), and just as importantly, when you absolutely shouldn’t. We’ll explore the history of rock licking, the legit reasons a geologist’s tongue can be as handy as a hammer, some classic examples (from salty halite to sticky clays), as well as the dangerous minerals to avoid. And if you’re cringing already – don’t worry – we’ll also cover clean alternatives that don’t involve turning your taste buds into lab equipment. By the end, you’ll know when licking makes sense, when it doesn’t, and how to be the kind of geologist who knows better than to lick arsenic. Let’s dig in (tongues out, please)!

A Brief History of Rock Licking

Geologists have been putting tongue to stone for centuries – it’s not just a weird modern habit. In the 18th century, before fancy labs and high-tech tools, early “rock stars” of geology literally tasted their way to mineral discoveries. One famous example: Italian geologist Giovanni Arduino described how different rocks and minerals had distinct flavors – some tasted sour or acidic, and others even “burned” the tongue[1]. He would sometimes heat rocks to bring out the taste, using his palate as an early geochemical sensor (talk about a taste test!). This may sound bizarre today, but back then it was a practical method. With no modern machines or textbooks, geologists had to rely on their senses – including taste – to identify specimens. As Ig Nobel Prize-winning geologist Jan Zalasiewicz quipped, “About 200 years ago, geologists were licking rocks to find out what they were… they did geology, at least in part, by taste. And it worked.”[2] Rock licking became a tried-and-true field technique passed down through generations of geologists (a sort of secret handshake… or tongueshake?).

Over time, the practice has become part of geology lore – a quirky trick veteran geologists perform without a second thought. Modern geoscientists still learn about it, often with equal parts fascination and revulsion. In fact, Zalasiewicz’s humorous essay on why geologists lick rocks won him an Ig Nobel Prize in 2023[3], shining a spotlight on this odd tradition. So if you see a geologist licking a rock, rest assured: they haven’t lost their mind – they’re carrying on an old-school field method with a rich history. But why would anyone do this in the first place? Let’s put this question under the magnifying lens (or rather, on the tip of the tongue).

Why Do Geologists Lick Rocks? (The Science Behind the Taste Test)

So, what do geologists achieve by licking rocks? It turns out the tongue is a surprisingly handy field tool. Here are the main scientific reasons behind rock licking – consider this section “rock licking explained” in earnest:

- To See What’s Inside – Moisture Reveals Detail: A dry, dusty rock can hide important features. Licking it (or otherwise wetting its surface) acts like a quick coat of varnish, making textures, fossils, and mineral grains pop out visibly[4]. The moisture enhances contrast and color, allowing subtle structures to stand out that you’d miss on a dry surface. Geologists often say a licked rock is easier to read – patterns of crystals or fossils become clearer when wet. In the field, carrying water or spit is easier than carrying a portable laboratory, so a little tongue action gives instant results. Zalasiewicz notes that licking is “an old trick of the field” – by wetting a rock, “the little bits of mineral and any bits of fossil in them can stand out more clearly”[4]. In other words, a quick lick can reveal what a cursory glance would miss.

- Taste Testing for Identification: Some minerals have distinct flavors, and geologists (being a bold bunch) will literally taste a specimen to identify it. The classic example is halite, better known as rock salt. It looks a lot like other clear minerals (quartz, calcite, gypsum), but none of those will make your tongue tingle with saltiness. One lick and that unmistakable salty taste confirms it’s halite[5]. Geology students quickly learn that you’ll never miss halite on an exam if you’re willing to lick the sample – there’s no mistaking salt! Similarly, halite’s chemical cousin sylvite (potassium chloride) can masquerade as halite in appearance, but a taste test gives it away: sylvite has an even more bitter, unpleasant flavor (often described as “pungent” and downright disgusting)[6]. In fact, bitter-tasting sylvite is a key field clue to distinguish it from common salt[6]. Geologists historically even tasted rocks for more subtle hints – early prospectors could sometimes detect trace minerals by slight bitterness or sweetness in a rock’s dust. (Fun fact: the mineral borax has a mildly sweet, alkaline taste, and was sometimes nibbled to identify it – though we don’t recommend casually eating your mineral samples!)

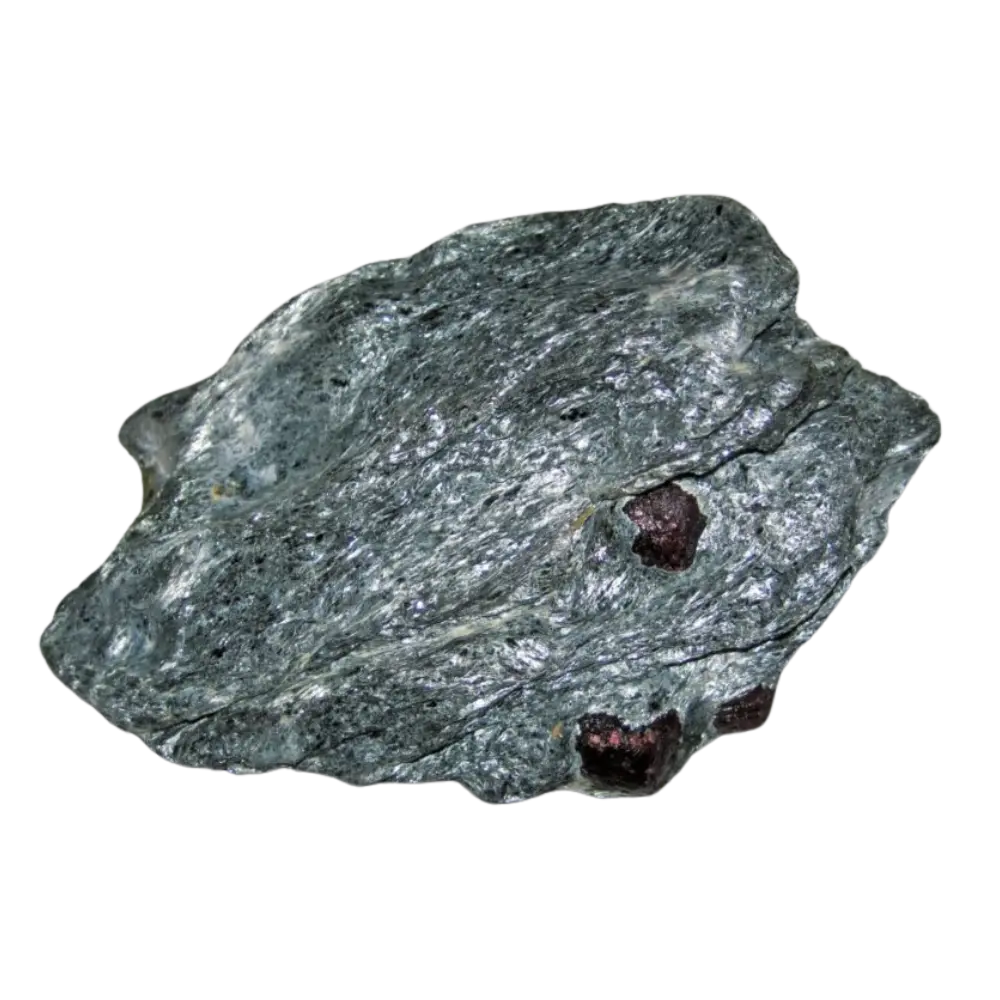

- The “Sticking” Test – Porosity and Clays: Not all diagnostic “tastes” are flavors; some are all about texture and physics. Geologists often use the tongue stickiness test to identify certain rocks and fossil materials. A classic scenario: you find a chunk of something that looks like bone – is it a fossil or just a rock? Give it a gentle lick. If it sticks to your tongue, it’s likely fossil bone[7]! Fossilized bone retains tiny pores from the original bone structure. When you touch it with a moist tongue, those pores create suction – the bone clings to your tongue like Velcro. Most ordinary rocks (or petrified wood, or other lookalikes) won’t do that[7]. Paleontologists in the field literally use this trick to quickly separate bone from stone. It might look goofy, but it’s effective – many a dinosaur fossil has been recognized by a scientist with a pebble “glued” to their tongue. Porous sediments and clays behave similarly: very fine-grained, dry materials will stick to a wet tongue because they absorb moisture. For instance, kaolinite (a type of clay) and certain clay-rich siltstones have no distinct flavor, but they will adhere to your tongue when dry[6][8]. Exploration geologists take advantage of this: if a rock has kaolinite or chalky clay, a quick lick test (or even just touching it to your lip) can confirm the presence of those clays by the sticky feel[8]. One geology blogger explains that minerals like chrysocolla and kaolinite “make up in texture what they lack in taste” – they will stick to your tongue, a dead giveaway[6]. Essentially, if it sticks, it licks (and tells you something about the rock’s porosity).

- Texture and Grain Size – The Grit Test: Sometimes, licking isn’t about taste at all but about using your mouth as a sensitive textural sensor. Geologists distinguish very fine sedimentary rocks by the “tooth test.” If you can’t visually tell claystone (mudstone/shale) from siltstone – they look and feel similar in hand – you might do the unthinkable: take a tiny nibble or scrape of the rock and grind it lightly between your teeth. (Yes, geologists will chew mud in the name of science.) The reason? Your teeth can feel the difference between ultra-fine clay and slightly gritty silt. Smooth like flour = clay; faint grit = silt. One veteran geologist describes it: “to tell the difference between mudstone and siltstone, you bite off a little piece and grind it between your teeth. The mudstone will be very smooth – sort of like a fast-food milkshake (they actually put clay in those!) – and the silt will be a little gritty.”[9] In other words, a shale (mostly clay) feels slick, whereas a siltstone crunches ever so slightly. This bizarre-sounding technique is actually quite effective – engineering geologists have used it for decades to estimate grain size distribution on the spot[10][11]. It’s like the geologist’s version of a sommelier swishing wine between their teeth, except the “vintage” might be 300-million-year-old mudrock.

In summary, geologists lick rocks not out of insanity, but utility. A bit of moisture (via tongue) can unveil a fossil’s texture, a mineral’s identity, or a rock’s grain size in seconds. It’s a field-expedient test – your tongue is always with you and never needs batteries! That said, as useful as it is, rock licking comes with major caveats. Before you run out to start sampling the flavors of your backyard stones, read on to learn why geologists also emphasize: lick with caution.

Rocks and Minerals You Can Identify by Licking (Salty, Sticky, and Gritty Examples)

To illustrate the above points, let’s look at some common rocks and minerals where a well-placed lick (or bite) truly comes in handy:

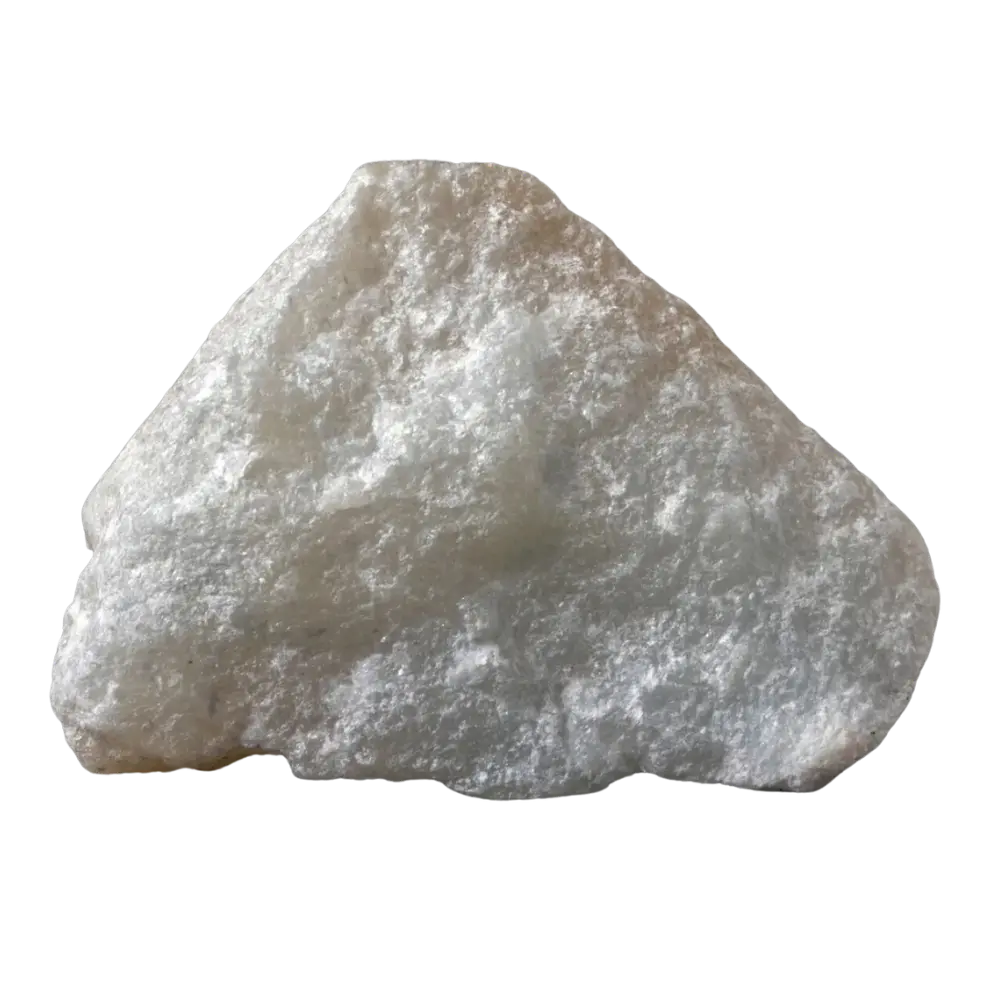

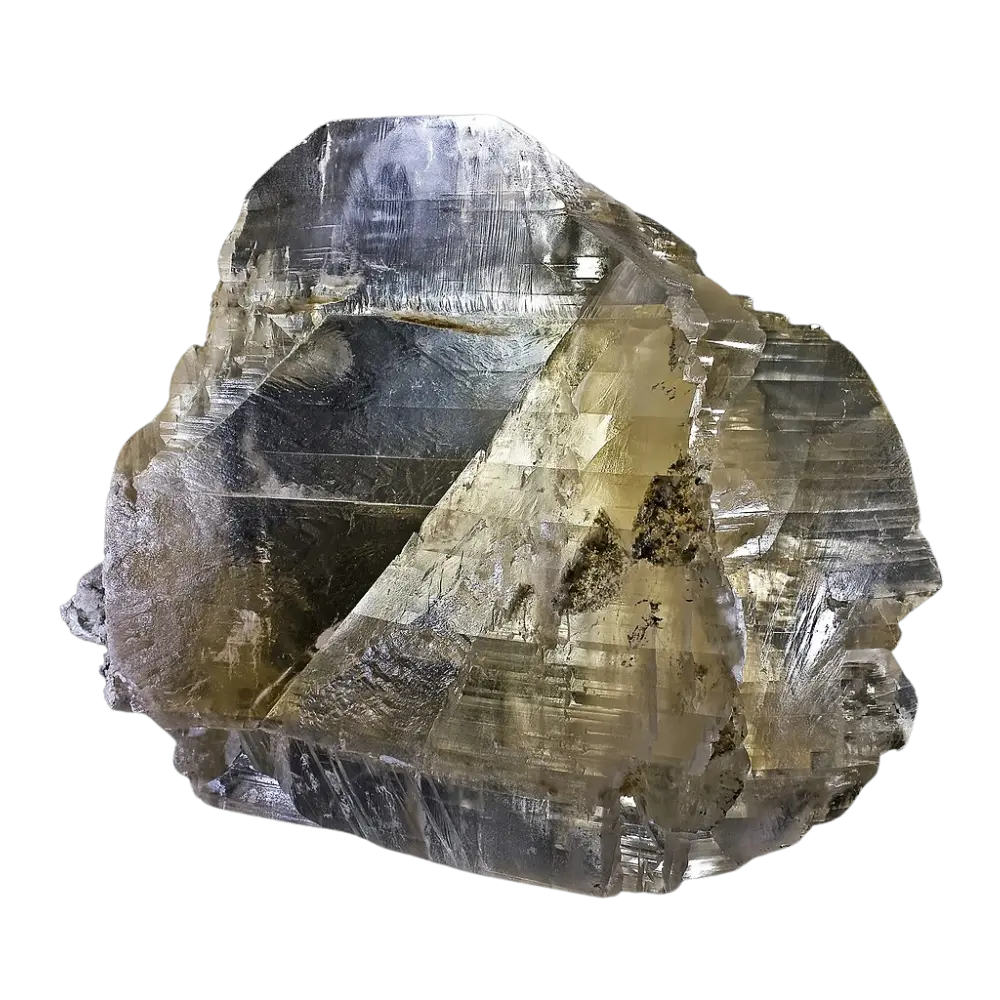

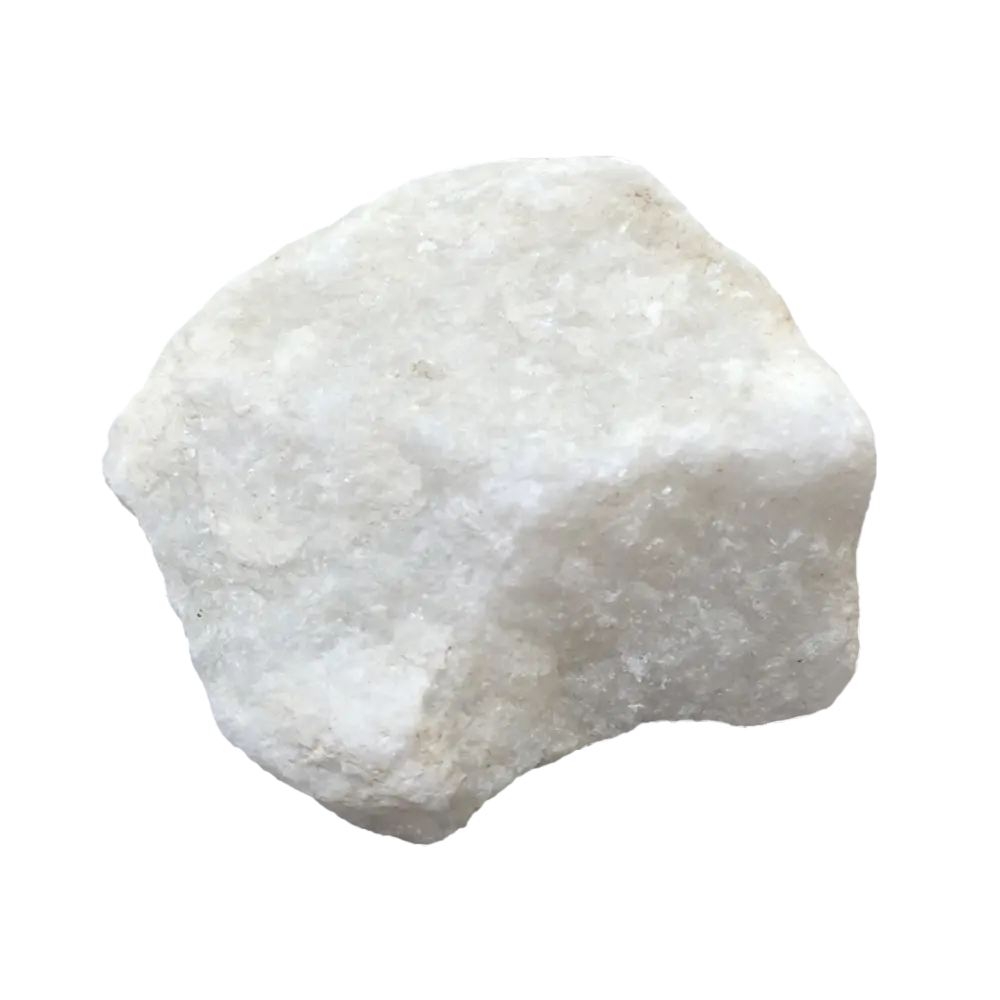

- Halite (Rock Salt) – Tastes Salty. The poster child of lickable minerals, halite is simply natural salt (sodium chloride). It often forms clear or white cubic crystals that could be mistaken for quartz or other minerals at first glance. But one lick and you know it – halite’s distinctly salty taste is immediately apparent[5]. Geology professors love to say, “you’ll never misidentify halite if you taste it.” True enough – none of those lookalike minerals will give you the salt flavor. (Just maybe make sure the sample is clean before you lick – more on that later!) In the field, licking a halite outcrop can quickly confirm that an area has evaporite salt deposits. Your tongue basically doubles as a salt detector.

- Sylvite – Bitter Imposter of Halite. Sylvite (potassium chloride) is another salt mineral that often occurs with halite. It looks similar – whitish, translucent – but if you put a piece on your tongue, you’ll want to spit it out. Sylvite has a strong bitter taste (some say like bitter salt or even slightly metallic) that is quite unpleasant[6]. This “yuck” factor is a diagnostic clue: geologists distinguishing halite vs. sylvite will do a careful taste test – salty = halite, bitter = sylvite[6]. Just a tiny tongue tap is enough to tell. It’s a quick differentiator when analyzing evaporite deposits. (Sylvite is also known as a key source of potassium for fertilizer – but again, as a “spice” it’s nothing like common salt!)

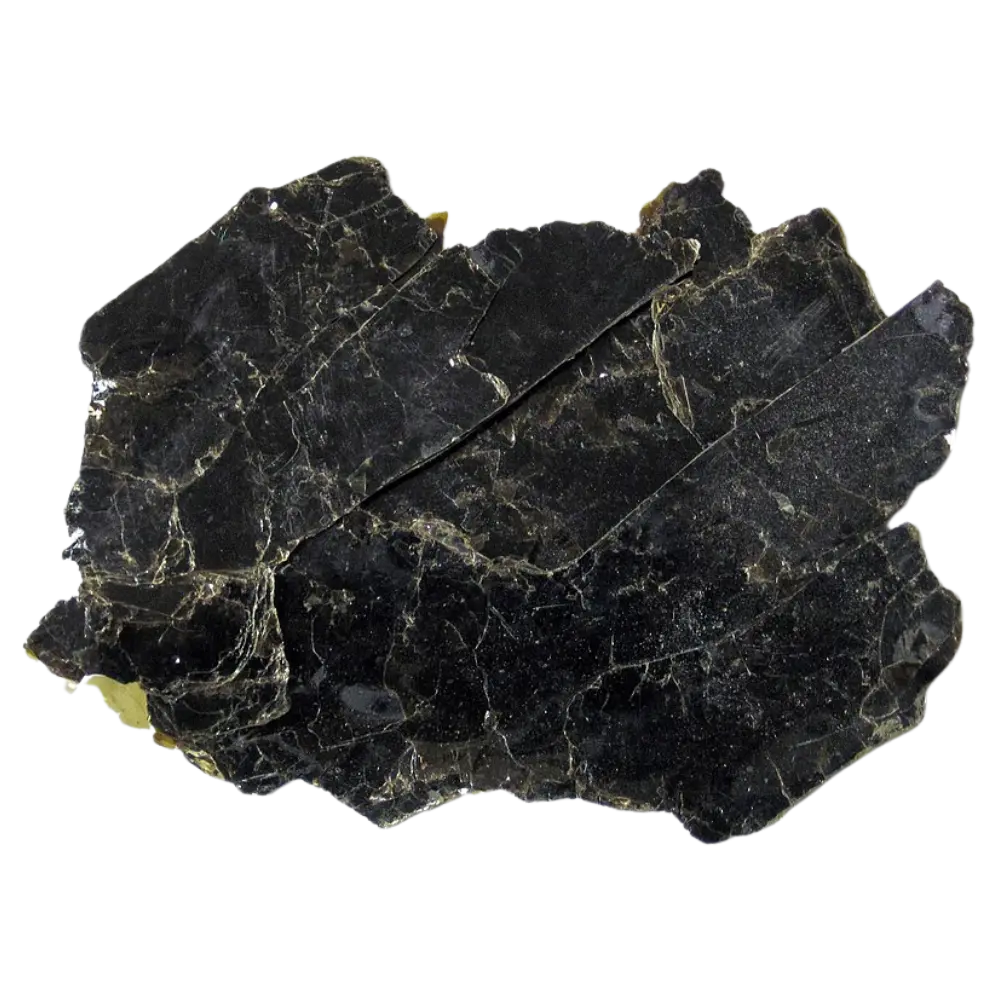

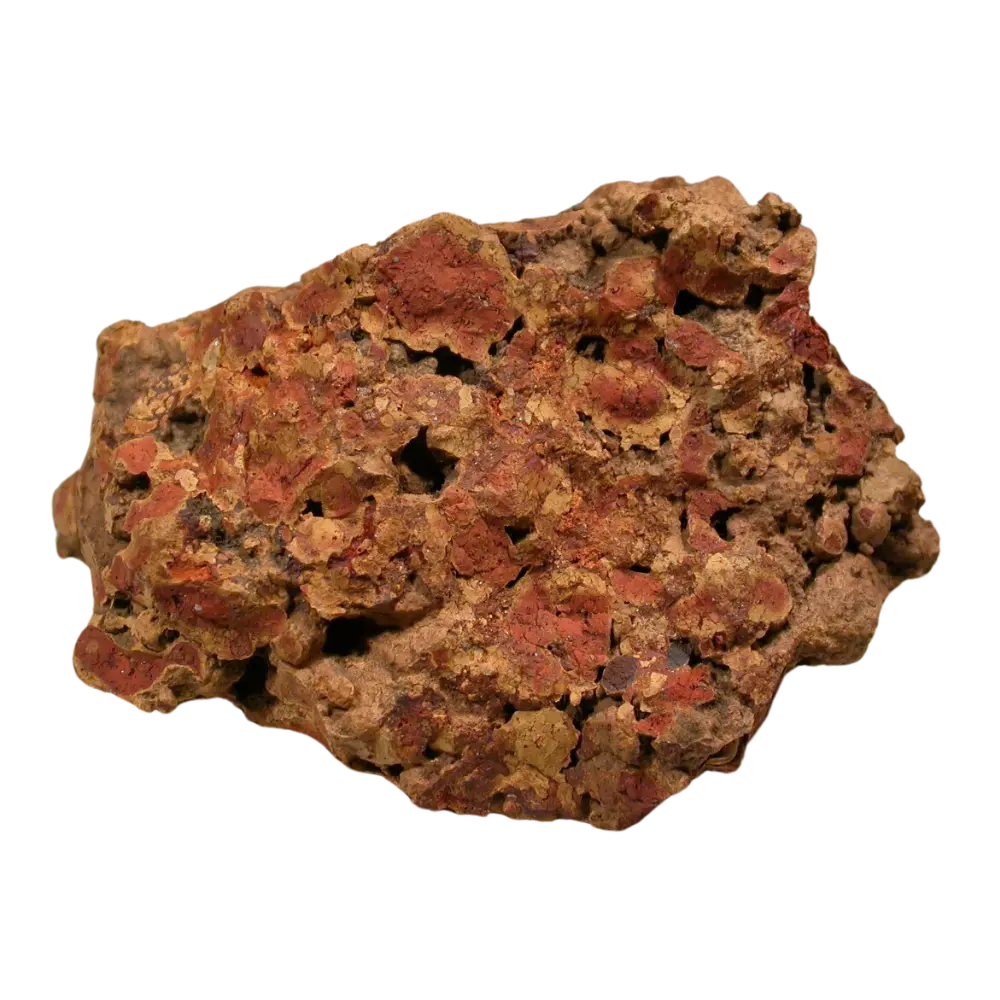

- Kaolinite and Clay Minerals – Stick, No Flavor. Kaolinite is a soft white clay mineral (famous as the main ingredient in porcelain and also for the name “China clay”). It doesn’t have a notable taste, but if you dab a dry kaolinite-rich rock to your tongue, it will stick. So will other clays like montmorillonite (the clay in bentonite) and certain hydroxide minerals. These minerals are extremely fine-grained and absorb moisture rapidly, so a dry sample will latch onto a wet tongue like a sponge[8]. Exploration geologists use this trick when evaluating hydrothermal alteration zones: if an altered rock sticks to the tongue, it likely contains clays (like kaolinite) that formed from weathering[8]. It’s cheaper and faster than waiting for a lab X-ray! The “tongue glue” effect also applies to chalky sediments (ever wonder why old-school folks might taste a bit of soil?). Of course, you could add water to the sample instead – but where’s the fun in that? (Kidding – please consider a drop of water as an alternative, as your dentist would prefer you not chomp clay all day.)

- Fossil Bone vs. Regular Rock – Porous = Tongue Stick. As mentioned earlier, licking can help verify if that weird chunk you found is fossilized bone. Real bone (even fossilized) is porous and will create suction on your tongue, making the piece momentarily stick[7]. Regular rocks or minerals in the shape of bone (like some limestones or petrified wood) won’t stick. This simple tongue test has saved countless paleontologists from tossing out real fossils or wasting time on mere lookalikes. Paleontology volunteers have been known to wander dig sites with bits of bone stuck to their tongue – a badge of honor in that world! One Utah museum paleontologist notes that with practice, “tasting his way through geological time” became second nature, and he’s managed to avoid anything truly nasty (barring the occasional fossilized dino droppings)[12]. Just remember: clean the specimen first – you never know what ancient critter last touched that bone.

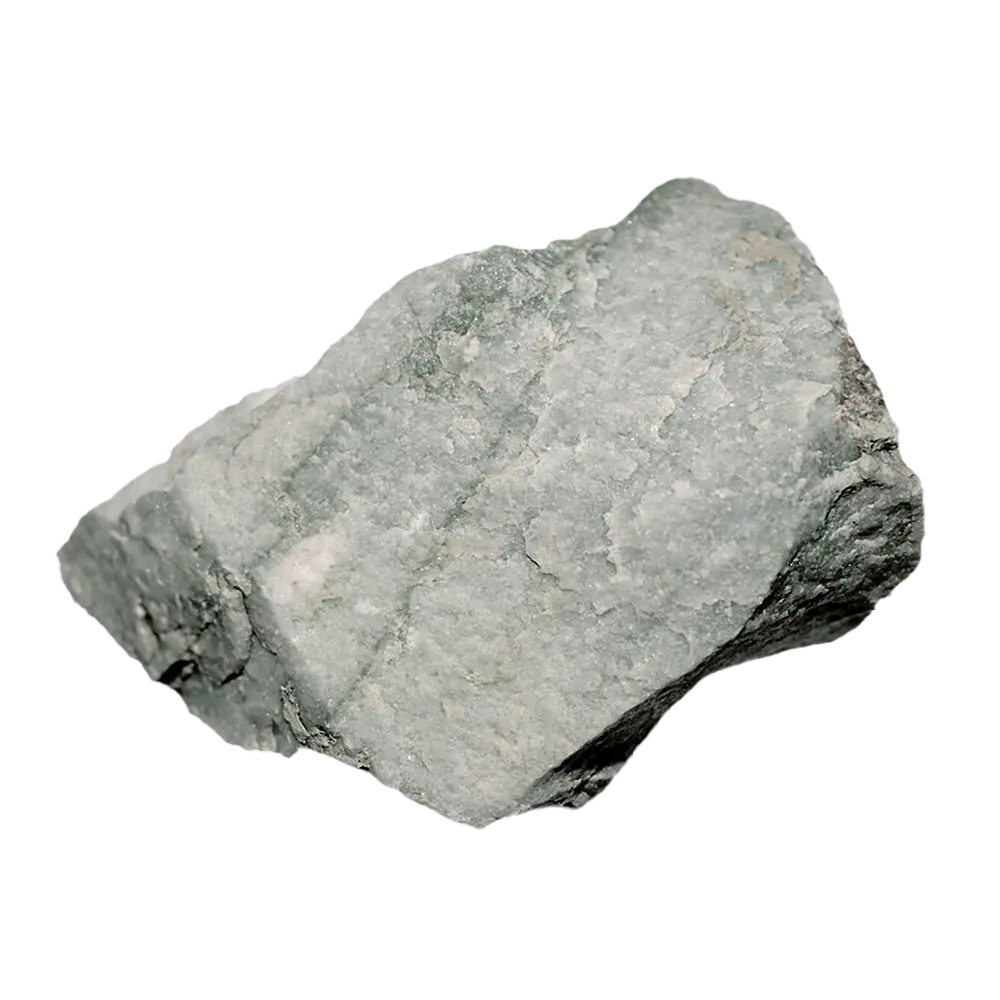

- Siltstone vs. Shale (Mudstone) – Gritty vs. Smooth. When visual inspection fails to distinguish very fine sedimentary rocks, the bite/chew test comes into play. Take a tiny piece (no larger than a grain of rice) and gently chew or grind it between your front teeth. If it feels gritty or sandy, even slightly, the rock contains silt-sized particles – it’s likely a siltstone[13]. If it feels completely smooth (no grit), it’s mostly clay – a shale or mudstone[13]. This works because silt grains (~0.05 mm) are just large enough for your teeth to detect, whereas clay particles are too fine. As one field geologist puts it, “siltstone will feel gritty against your teeth, shale won’t”[13]. This method is especially useful at a fresh outcrop when trying to quickly gauge the sediment size in a mudrock formation. It’s also a source of endless entertainment when a group of geology students is seen munching rocks like popcorn on a field trip. (Pro tip: do not swallow. Spit that rock dust out after grinding – your digestive system didn’t sign up for a geology degree.)

These examples show that the human senses – even taste and touch – can be clever tools in geology. Licking or biting a rock, done judiciously, can reveal immediate clues about mineralogy and texture that might otherwise require chemical tests or microscopes. It’s hands-on (tongue-on?) science at its simplest. However – and this is crucial – knowing when not to lick is just as important. Some rocks will bite back in a far more dangerous way. So before you start sampling everything like a buffet, let’s talk safety.

Dangerous Minerals to Avoid: Rocks You Should Never Lick

Here’s the part where we put on our serious face (and maybe a hazmat suit). While many rocks are benign or even edible (salt licks, anyone?), some are toxic or hazardous. Geologists are trained to know the difference. You do not want to lick or ingest certain minerals, because you could be exposing yourself to poisons or radiation. Below is a list of minerals and rocks that you should never lick (no matter how curious you are):

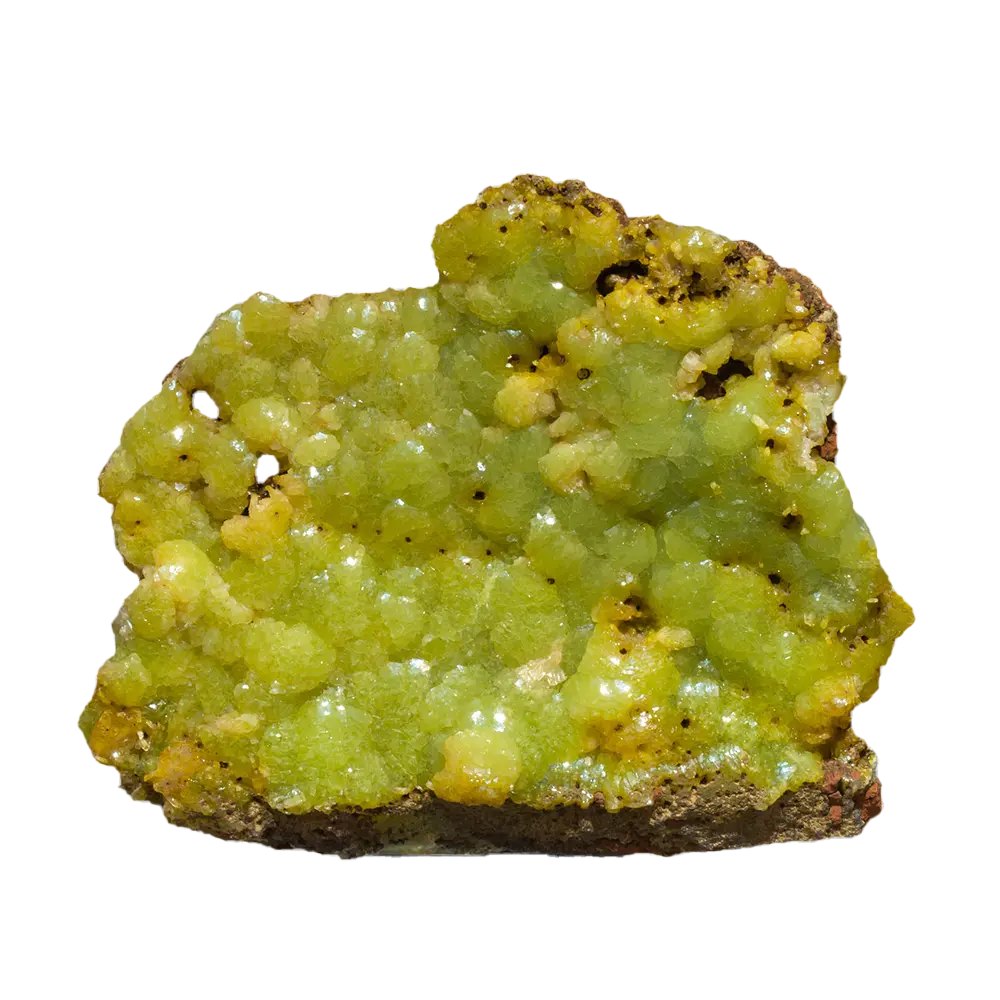

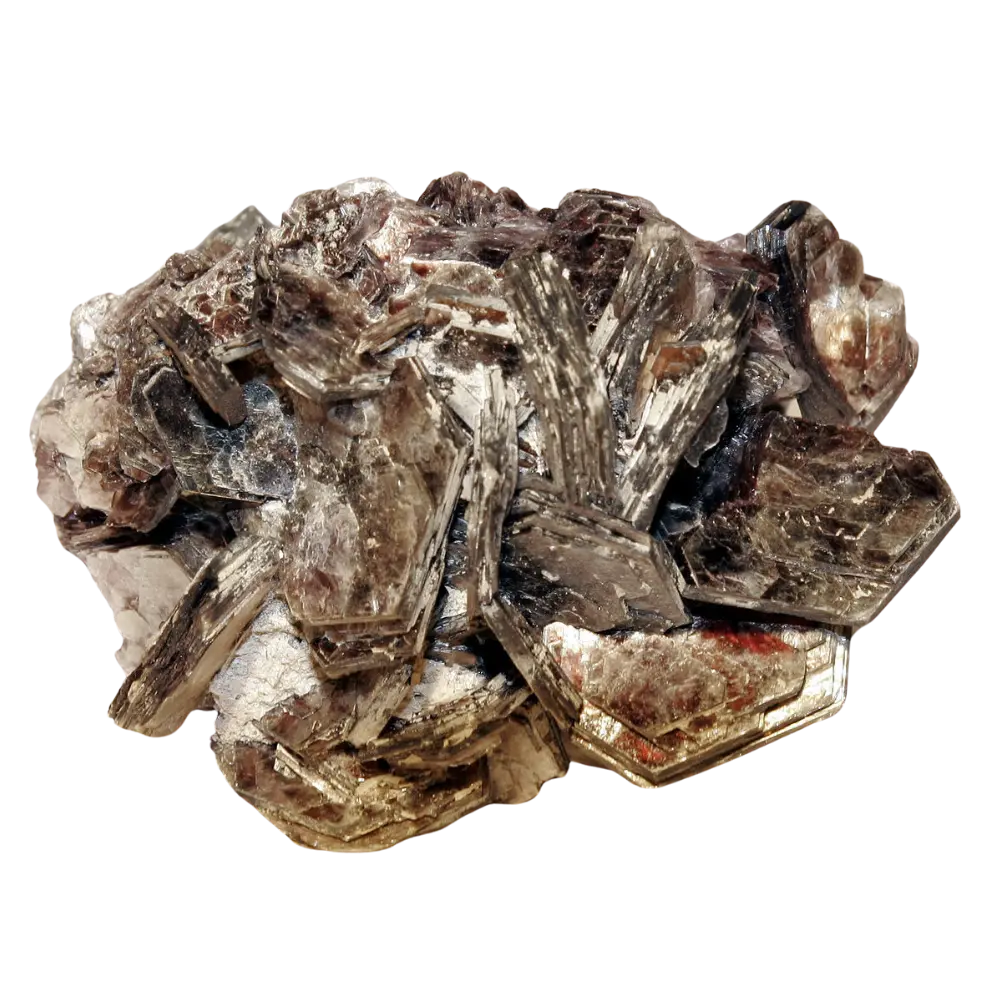

- Arsenic Minerals (Arsenopyrite, Realgar, Orpiment): As a rule, if a mineral’s chemistry involves arsenic (As), keep it off your tongue. Arsenopyrite (FeAsS) is a common arsenic ore – it won’t taste like much, but it can release arsenic compounds if dissolved. Same with the bright orange-red arsenic sulfides realgar and orpiment. Geologists know these are highly poisonous substances[14]. In fact, arsenic was infamous as a historical poison (“inheritance powder”), precisely because it’s colorless, tasteless, and deadly[14]. Licking an arsenic-bearing rock could transfer toxic traces to your body – a risk not worth taking. To identify these minerals, geologists rely on visual cues or instruments, not taste. So if you suspect arsenic, do not do the lick test! (Your tongue will thank you, and you’ll avoid possible acute arsenic poisoning.)

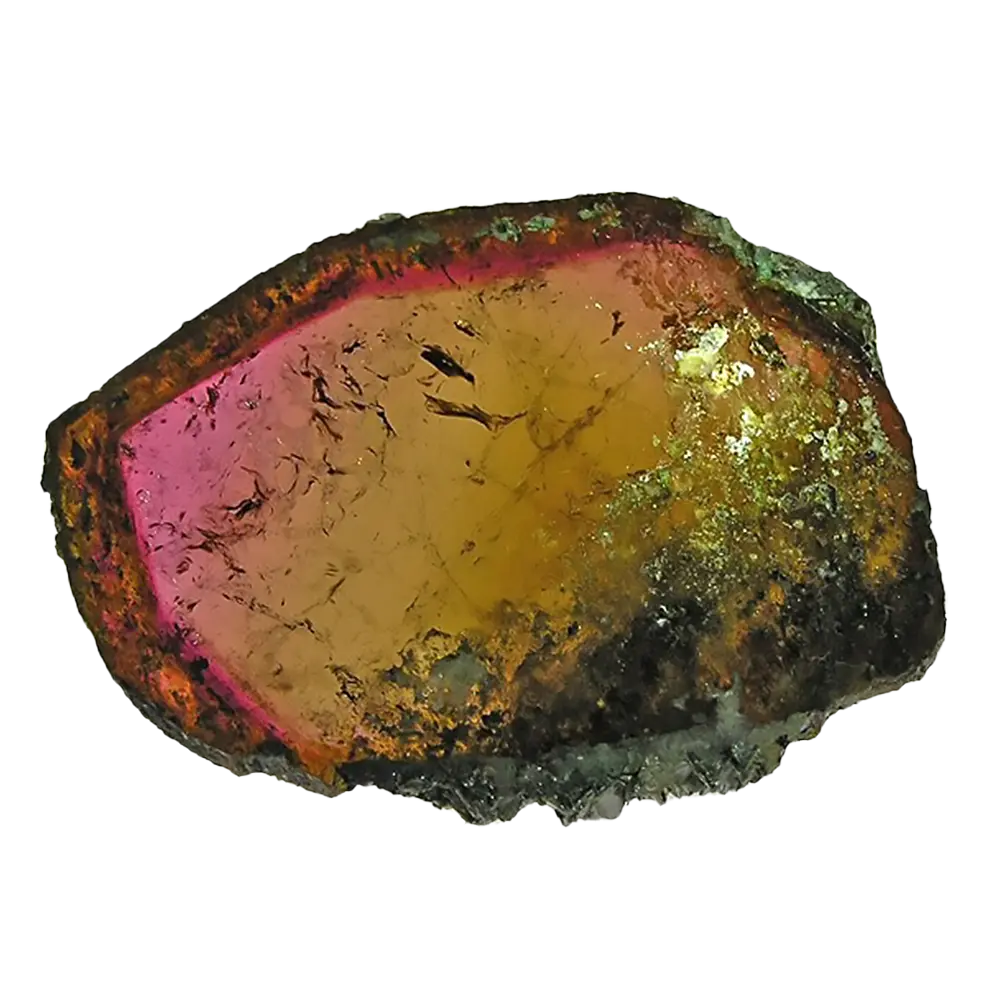

- Mercury Minerals (Cinnabar, Realgar’s cousin): Cinnabar (HgS) is a mercury sulfide, typically a deep red mineral. It’s actually somewhat tempting to lick because it looks like red candy or cinnamon (indeed, “cinnabar” sounds like cinnamon – but don’t be fooled!). Mercury is extremely toxic. While solid cinnabar doesn’t vaporize at room temperature, handling or licking it can still be dangerous – mercury can absorb through mucous membranes or be inhaled if any dust is released[15]. Historically, cinnabar miners had tragically short lifespans from mercury exposure[15]. So, never lick or taste cinnabar or any mercury ore. The risk of mercury poisoning (tremors, psychosis – “mad hatter” syndrome) is very real[15]. Identification of cinnabar is done visually (it has a red color and high density) or with chemical tests, not by flavor. The only thing you’d get from tasting cinnabar is a one-way ticket to the doctor.

- Radioactive Minerals (Uranium Ore): Radioactive rocks and minerals are a definite NO for the lick test. Uranium-bearing minerals like uraninite, autunite, torbernite (the green uranium “mica”) and others may not poison you chemically, but they emit radiation. Putting them in your mouth dramatically increases your exposure (alpha particles don’t penetrate skin, but they sure can wreak havoc internally if ingested). One geologist’s rule: if it’s radioactive, use a Geiger counter, not your taste buds. For example, autunite is a yellow-green crystal containing uranium – beautiful, but handle with gloves and obviously do not lick. Besides radiation, many uranium minerals are also heavy-metal toxins if dissolved. As a Washington State geology bulletin drily notes, uranium and other radioactive elements decay and release “invisible cell-destroying radiation”[16] – not something you want in your mouth. So if you suspect a specimen might be uranium ore (common in certain sandstones or pegmatites), keep it out of your mouth (and pocket). Geologists usually identify these by context and sometimes by using UV light (some uranium minerals fluoresce) or radiation detectors.

- Lead Minerals (Galena, Cerussite, etc.): Galena (PbS) – the metallic lead sulfide – has a bright metallic luster and a sweet name (it resembles lead “glance” crystals). While not highly soluble, any lead compound is not something you want to ingest. Lead can accumulate in the body and cause neurological damage. Cerussite (lead carbonate) is even more soluble and can definitely poison you if you get it on your hands or in your mouth. A geology blogger advises leaving lead ore minerals “to your other four senses” – in other words, do not taste them[17]. There’s no good reason to lick galena; it’s easily identified by its cubic cleavage and high density. And cerussite might have a sweetish taste (lead acetate was historically called “sugar of lead” – yikes), but tasting it would be a terrible idea. So, with anything lead-bearing: no licking, wash your hands after handling, and keep it away from kids or pets who might mouth it[18].

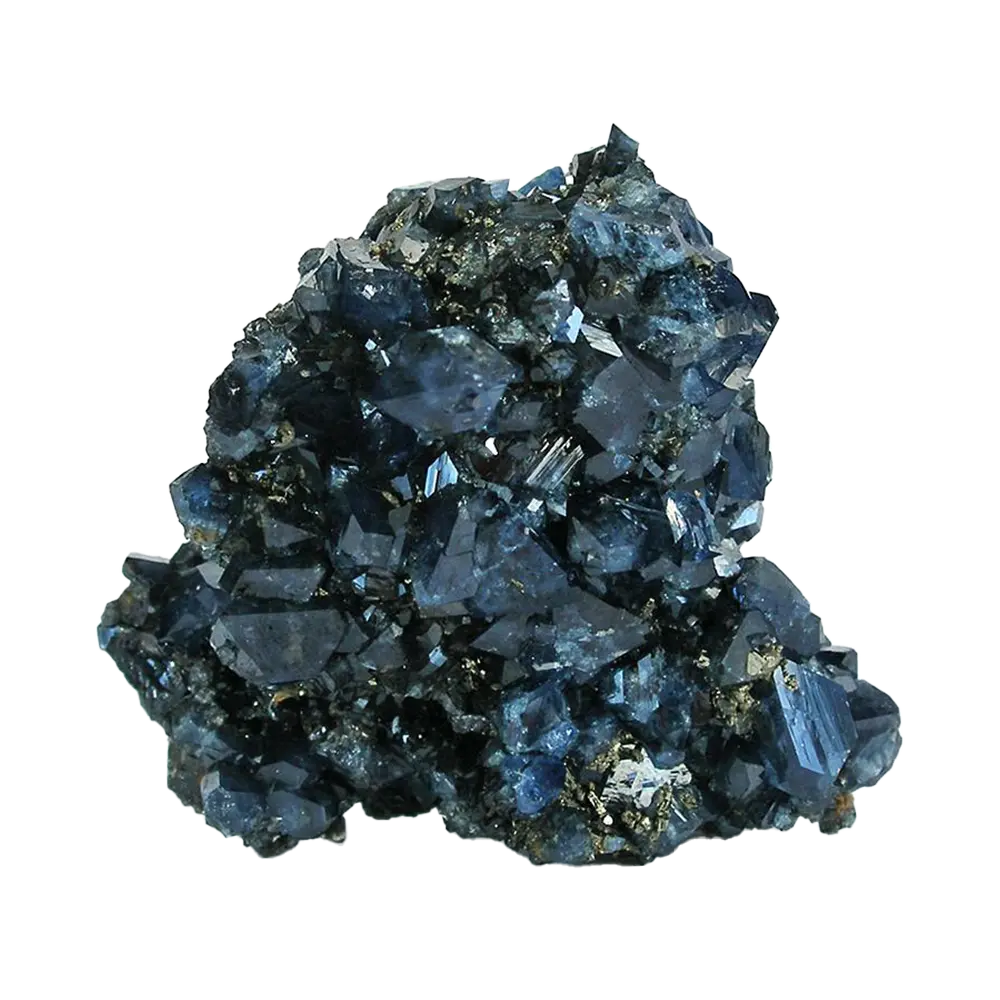

- Copper Minerals That Dissolve (e.g. Chalcanthite): Chalcanthite is a vibrant blue crystal (copper sulfate) that literally dissolves in water. It has a surprisingly sweet, astringent metallic taste – and guess what, it’s poisonous[19]. Copper sulfate is used as a pesticide/fungicide; it’s not meant for human consumption. Any water-soluble copper mineral (chalcanthite, antlerite, etc.) can leach heavy metals. So even if it looks pretty and seems like it might taste like blue raspberry (it won’t), do not lick! In general, never lick blue or green minerals – they often contain copper or other metals. Malachite and azurite (copper carbonates) aren’t very soluble, but it’s best not to risk ingesting copper either (it can cause serious gastrointestinal upset and liver damage in quantity). When in doubt, assume a colorful mineral could be toxic and keep your tongue off it.

- “Don’t Lick the Rocks” Exceptions: It should go without saying, but minerals like asbestos (chrysotile, etc.), powdery silica (like crysotbalite), or anything that is harmful to inhale should also not be licked – mainly because you could inhale the fibers or dust. Also, any rock that has been exposed to possible contamination (say, from industrial sites, pesticides, animal waste) is a bad candidate for mouth contact. Even if the rock itself is harmless quartz, the stuff on it might not be. Common sense and caution go a long way: when in doubt, do not put it in your mouth. Your health is more important than confirming a hunch with a taste.

In modern geology training, students are taught to treat unknown samples as potentially hazardous. One mineral lab manual bluntly states: “For safety reasons, please do not taste your samples. While this has been fairly common in the past, it is no longer a good practice… With mineral kits that must be shared, it’s not safe for you or others.”[20] In other words, licking might have old pedigree, but we’ve gotten wiser about the risks. Aside from chemical toxicity, consider biological hazards: the dirt and crevices on a rock can harbor bacteria or parasites (some nasty microbes or, say, fox tapeworm eggs) that you really don’t want in your mouth[21]. One experienced geologist noted that the danger in tasting rocks often isn’t the rock itself but “possible bacteria, fungi, or Echinococcus (parasite) from the soil”[21]. Grossed out? Good! That’s your survival instinct kicking in.

Know your enemy. Unless you’re 100% sure a mineral is safe (and you have a darn good reason to lick it), it’s best to err on the side of caution and not lick. Use other methods to identify it. No piece of data is worth poisoning yourself. Geologists carry a long list in their brains of “things never to lick,” and now you have a glimpse of that list too.

Field vs. Lab: Licking Rocks in Context

It’s worth noting that rock licking is mostly a field technique – and even then, used sparingly. The etiquette and protocols differ between an outdoor field expedition and an indoor laboratory or classroom:

- In the Field: When you’re out mapping in the wilderness, you often have limited tools at hand. The appeal of the lick test is that it’s quick and uses what you’ve got. Many veteran field geologists will casually lick a rock to get a fast clue about its nature – it’s almost second nature. Fieldwork culture has traditionally accepted it (some might even say it’s a rite of passage to lick your first rock). Zalasiewicz notes that many of his colleagues still do it, even confessing that they can recognize certain sediment layers by taste alone[22] – old-school skills from “the olden days.” In fieldwork, you’ll also see geologists spitting on rocks or using a squirt from a water bottle to wet the surface, achieving the same effect without direct tongue contact[23]. (A popular field saying: “Don’t lick it if you can spit on it.”) Spitting or dropping water is especially preferred if you suspect something might be dubious to ingest – you still get the “wet look” to see textures[23]. Additionally, in field identification, geologists augment their senses with other simple tools: a hand lens (magnifier) is constantly used to inspect minerals up close (far more than licking in most cases)[24]. They’ll also use hardness picks, streak plates, and dilute acid (for fizz testing carbonates) on site if available, which reduces the need to ever put the sample in their mouth. In essence, licking is a supplemental trick in the field geologist’s toolkit – handy in a pinch, but not the primary method for most identifications. And good field geologists are picky about when to lick: they avoid licking anything suspect (as we detailed above), and they typically lick only freshly broken surfaces of a rock[21]. Breaking the rock exposes a clean interior (free of weathering, dirt, lichens, etc.), which is not only better for observation but also safer to taste if one is going to. Never lick weathered, dirty surfaces – you’re just sampling the local dirt and microbes at that point, not the rock itself[21].

- In the Lab or Classroom: Indoors, the standards are very different. Geology labs nowadays generally prohibit licking or tasting of specimens, for all the reasons we’ve mentioned. In a classroom setting, samples are shared among many students, and it’s just unsanitary (and potentially unsafe) for everyone to be licking the same rocks. Professors will explicitly tell students “do not taste your samples” – even if some of them may chuckle knowing that geologists used to do that[20]. Instead, students learn to identify halite by its cubic cleavage and softness, or by rubbing it and maybe smelling (salt has no smell though). They learn to distinguish clays by making a little wet paste and feeling it between fingers (rather than on the tongue). The only time you might see taste used in a teaching lab is if the instructor prepares a controlled demonstration – e.g. passing around clean halite chips for everyone to touch to their tongue once, or using “safe to taste” materials in a supervised way[25]. Even this is becoming rare. For instance, one educational guide from the Mineralogical Society suggests using things like rock candy to simulate mineral tastes in outreach events – because it’s safer and more fun for kids[26][25]. In professional labs (or museum curation), tasting specimens is a big no-no. Not only for personal safety, but also to avoid contaminating pristine samples. There are so many better analytical methods available (from streak tests to X-ray fluorescence) that licking is unnecessary in a lab environment. As one Stack Exchange geology contributor put it: tasting was common in the past, but “it is no longer a good practice with mineral kits that must be shared… for your own safety and that of others.”[20] Modern geologists pride themselves on safety, so you won’t see them French-kissing rocks in the lab – they’ll use a microscope or spectrometer instead.

In short, context matters. In the field, when faced with a mystery rock and limited tools, a geologist might carefully employ the old lick test (after considering the safety of doing so). In the lab, they’ll stick to other diagnostic techniques. The tongue is a last resort indoors, and even outdoors it’s used with discretion. The cliché of geologists licking every rock they see is exaggerated – they only do it when it provides useful info and when it’s safe. The days of the carefree rock-licking professor have largely given way to a more cautious approach (no one wants to be “that student” who licked the toxic mineral in lab). As science advances, the need for taste-testing has diminished, but the legend (and practical knowledge) lives on.

Beyond Licking: Safer Alternatives for Rock Identification

So, what can you do instead of licking if you’re a sensible geologist (or an amateur rockhound) who wants to identify rocks and minerals? Fortunately, geoscience offers a rich arsenal of alternative tests and tools that don’t involve potential poisoning or weird looks from your friends. Here are some lick-free identification methods every geologist uses:

- Hand Lens / Microscope: The hand lens (10× magnifying glass) is a geologist’s best friend[24]. Carry one in the field: it lets you examine mineral grains, crystal shapes, and fine textures up close. Often, what might have required wetting the rock to see, you can observe with magnification. Is that glittery fleck muscovite mica or halite? Look for cleavage or crystal form with the lens. In a lab, a binocular microscope can reveal even more detail. Your eyes (aided by magnification) can usually distinguish things like pores, grain size, or tiny fossils without involving taste.

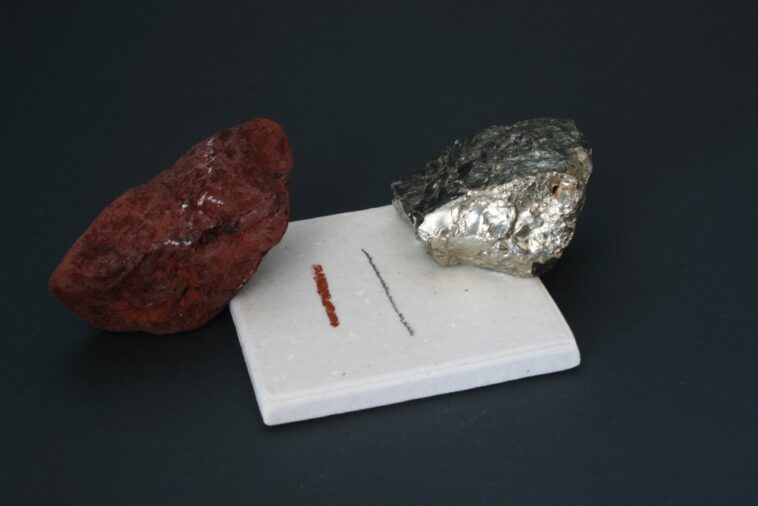

- Streak Test: Instead of tasting for a mineral (please don’t lick that hematite), use a streak plate – an unglazed porcelain tile. Scratch the mineral on the plate to see the color of its streak (powder). This is a classic test: for example, hematite might appear black or metallic gray, but it always leaves a telltale red-brown streak[27]. No need to taste iron oxide (which has no flavor you’d enjoy anyway) – the streak tells the tale. Similarly, minerals like chromite vs. magnetite can be distinguished by streak color, all without ingesting a thing.

- Hardness (Scratch) Test: The Mohs hardness test can identify minerals by what can scratch what. For instance, halite is very soft (2.5 hardness) and can be scratched by a fingernail – that’s a quick clue that it’s not quartz (which would scratch your fingernail). If you had any doubt between halite and, say, gypsum or calcite, a hardness test can help. True, tasting halite is faster, but a scratch test is completely safe and leaves your sodium levels unaffected. Geologists carry small hardness picks or use common objects (glass, steel nail) to test hardness in the field.

- Chemical Tests (Fizz and others): A very useful non-taste test is the acid fizz test. Geologists drop dilute hydrochloric acid (or even vinegar) on a rock to check for carbonate minerals like calcite. If it fizzes (bubbles of CO₂), it’s carbonate-rich limestone or marble; if not, maybe it’s silicate. This test can distinguish, for example, calcite vs. quartz (try acid, not tongue). There are also chemical spot tests and kits for specific ions (like putting a drop of silver nitrate on a rock to test for chloride if you suspect halite – it will precipitate white AgCl). These are more lab-oriented, but the point is: chemistry can often do more safely what taste would only hint at.

- Water and Wetting Tests: If the main reason to lick is to wet the rock, just use water! Geologists often carry a water bottle or even a little eyedropper to wet a surface. A water drop test on a porous rock can be revealing: for instance, dropping water on clay-rich soil will be absorbed slower or faster depending on texture. Water can also help bring out features (just as spit or licking would) but in a far more hygienic way. You can even wet your finger and touch it to the rock, instead of tongue-to-rock; then feel the finger for any texture or residue (some clays will feel sticky on your fingertip too). This way you spare your taste buds entirely.

- Tools and Tech: Modern field kits might include a portable UV lamp (some minerals glow distinct colors), a magnet (to test magnetism of a mineral like magnetite vs. hematite), and even a portable Raman or XRF analyzer for the high-tech crowd. While these aren’t as accessible to hobbyists, they show that we have instruments to identify composition that make tasting obsolete. But even simple tools like a thermometer (to test if a rock is unusually warm from radioactivity – though that’s extreme) or a radiation detector are all part of doing things safely. The rock will not hide its identity if you know how to ask in the right ways!

- Consult References & Guides: Often, identifying a rock doesn’t require any bodily contact at all – just careful observation and comparison to reference materials. Field guides, mineral charts, and apps can help you narrow things down by color, crystal form, context (geologic setting), etc. For example, if you’re in a salt flat region, a clear cubic mineral is likely halite – you don’t have to lick it to be sure (though you might anyway because it’s so temptingly diagnostic!). Education and experience can replace the need for taste; seasoned geologists can often tell by looking (or at most, by smelling or touching) what a novice might be tempted to lick.

There’s always an alternative to licking if you have doubts. The tongue is a tool of convenience, not necessity. Geologists lick rocks mostly when other methods are inconvenient at that moment. But if you’ve got the time and tools to spare, it’s usually wiser to use a streak plate or hand lens. And if you’re teaching newcomers or kids about rocks, maybe skip the licking part and stick to demonstrations with safe analogues (like that rock candy trick for halite). It’s all about balancing curiosity with caution.

Conclusion: A Little Lick Goes a Long Way (But Know When to Say “When”)

By now, you’ve learned that the strange habit of rock licking is grounded in genuine scientific utility – it’s not just a party trick or a dare among geologists. In the right moments, a lick can save the day: revealing a fossil, identifying a mineral like halite in an instant, or distinguishing between similar-looking rocks out in the wild. It’s part of the geologist’s toolkit, handed down from the early days of the science. However, you’ve also seen the flip side: plenty of reasons not to lick every rock in sight. With modern knowledge of toxicity (arsenic, mercury, etc.), plus the availability of safer techniques, we must use our heads before using our tongues.

So, when does licking make sense? It makes sense when you’re in the field, faced with a benign-looking sample, and you need a quick texture or taste clue – and you’re confident it’s safe (e.g. that white crystal is likely halite, that bone fragment might stick). A tiny lick in such cases can be the quickest way to “diagnose” the rock. When doesn’t it make sense? Whenever the rock could contain something harmful, or when alternative methods are at hand. If you even suspect a mineral could be dangerous (or just plain gross), keep your tongue in check. No amount of geologic insight is worth ingesting toxins. Likewise, in a classroom or lab with plenty of tools and reference material, licking is an unnecessary risk and generally frowned upon.

Ultimately, the best geologists have a well-calibrated sense of judgment to go with their sense of taste. They know when to use each tool – be it a mass spectrometer or a moist tongue – to get the information they need. They also know how to look really cool in front of students by casually licking a rock and declaring, “Yep, that’s siltstone,” but only because they genuinely know it’s safe and effective to do so in that moment. Now you know the secrets behind this practice. You can chuckle the next time someone jokes about geologists having “rocks in their head” – you’ll reply that actually, it’s rocks on their tongue, and there’s a good reason for it! Just as importantly, you won’t be the clueless newbie who licks the arsenopyrite (please don’t be that person).

So go forth and do geology with both wisdom and humor. Taste the world’s geology – figuratively, if not literally. And remember: be the kind of geologist who knows exactly when to lick a rock and when to keep your tongue firmly in cheek (and away from the arsenic). Happy rock hunting, and may all your identifications be deliciously accurate!

For more tips on field methods and the tools geologists use (that don’t involve taste buds), check out Geoscopy’s geology tools and field methods hub. Our goal is to equip you with all the knowledge to do smart, safe, and effective geology – no unwanted aftertaste required.[4][2]

[1] [4] [22] Licking tasting and eating rocks? – ABC listen https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/scienceshow/licking-tasting-and-eating-rocks/103287542

[2] [9] Saluting Science’s Silly Side, Virtually

https://www.sciencefriday.com/segments/ignobel-awards-virtual/

[3] Smart Toilets and Licking Rocks: Ig Nobel Prizes Celebrate Strange Scientific Achievements

[5] [6] [13] [17] Rocks: when to lick, when not to lick: med_cat — LiveJournal

https://med-cat.livejournal.com/1051091.html

[7] [12] Why Do Geologists Lick Rocks? | IFLScience

https://www.iflscience.com/why-do-geologists-lick-rocks-70107

[8] [19] [25] [26] Demonstrations.indd

https://mineralseducationcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/mineral_taste_test_0.pdf

[10] [11] [21] [23] geology – When can taste be used to help identify rocks? – Earth Science Stack Exchange

https://earthscience.stackexchange.com/questions/1084/when-can-taste-be-used-to-help-identify-rocks

https://www.dmns.org/catalyst/fall-2024/earths-poisonous-minerals

https://www.facebook.com/groups/beautyforthebeholder/posts/1445276046428174

[20] Physical Properties of Minerals – Laboratory Manual for Earth Science

https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/geolmanual/chapter/overview-of-minerals/

[24] Essential Tools for Successful Field Geology

https://geoscopy.com/field-geology-101-essential-tips-and-tools-for-successful-fieldwork/

[27] Glad You Asked: How Do Geologists Identify Minerals? – Utah Geological Survey

https://geology.utah.gov/map-pub/survey-notes/glad-you-asked/how-do-geologists-identify-minerals