In the heart of the 20th century, the American Midwest was the undisputed centre of the industrial universe. Cities like Detroit, Flint and Kenosha were more than just municipalities; they were giant, rhythmic engines of production. Inside the sprawling complexes of the Big Three, Ford, General Motors and Chrysler, thousands of workers moved in a synchronized dance to assemble the machines that defined the American Dream. One of the products of this dream? Fordite.

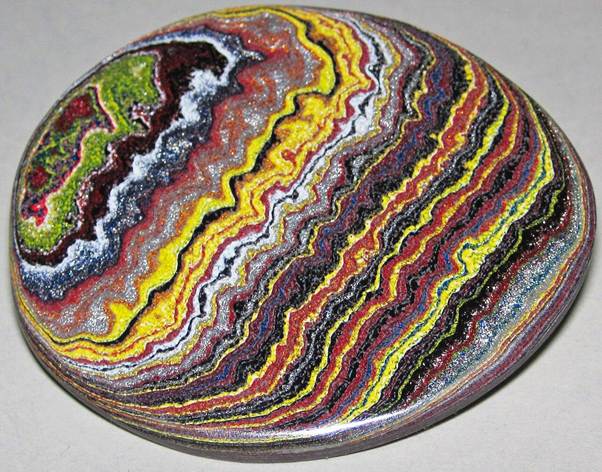

Amidst the heat, the sparks of arc welders and the relentless clatter of the line, something accidental, but strangely beautiful, was growing. It wasn’t a car, it wasn’t even a new car part. Detroit car manufacturers stumbled on a byproduct of the painting process. A vibrant, multi-layered “slag”, almost mineral-like substance, that we now know as Fordite.

Today, Fordite is a prized material for jewellers and historians alike. But to understand its value, we have to look back at the messy, hand-sprayed history of the automotive paint booth.

How industrial waste became something beautiful

The story of Fordite begins in an era before automation. Today’s car factories are sanitised, robotic environments where paint is applied by machines with microscopic precision. But from the 1920s through the late 1970s, painting a car was a visceral, human task.

The crucial nature of painting skids

In this era, when a steel car body was moved into the paint bay, it sat atop a heavy metal frame known as a “skid” or a “carriage.” These skids moved along tracks through the spray booths. As the painters, armed with compressed air guns, coated the fenders and hoods in the popular colours of the day, with a significant amount of “overspray” missing the car entirely.

This excess paint drifted downward, coating the skids, the tracks, and the structural supports of the bay.

What is Fordite really? Understanding the curing process

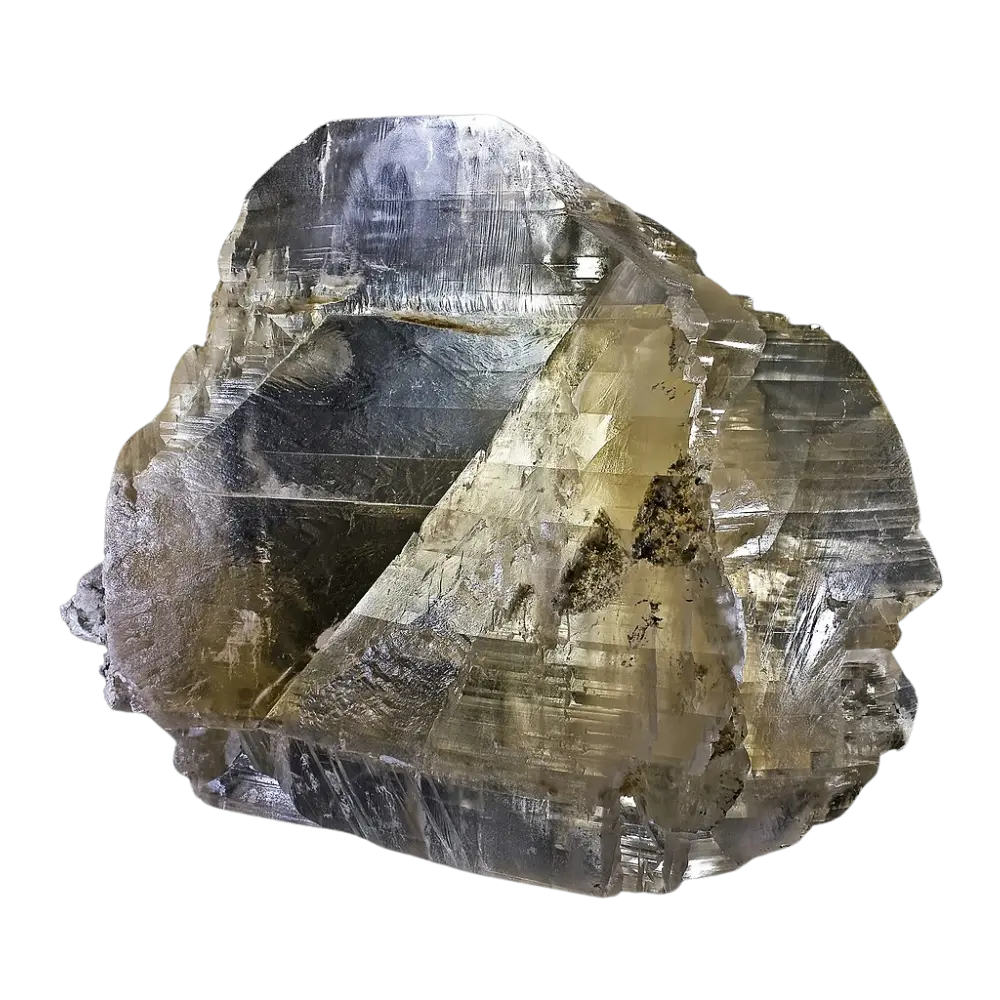

A single layer of wet paint isn’t Fordite. The transformation happened in the bake ovens. After each coat was applied, the entire assembly, meaning the car and skid together, was rolled into massive industrial ovens to “flash” or cure the paint at high temperatures. This hardened the enamel into a durable, ceramic-like finish.

Then, the next car would roll in. Perhaps it was a different model, or a custom order in a different colour. These manufacturing sites would move pretty quickly and dynamically to keep up with demand. Another layer of overspray landed on the already-hardened layer, and it went back into the oven. Over decades, these layers grew into thick, stony crusts, sometimes reaching several inches in depth.

This crust would soon be known as the Fordite “stone” we know today.

How Fordite became a sought-after material

For the factory managers of the 1950s, Fordite wasn’t a treasure; it was a mere industrial nuisance. As the buildup on the tracks grew thicker, it began to narrow the passage for the cars or even jam the wheels of the skids. Periodically, the line would be shut down for maintenance, and workers would take hammers and chisels to the tracks, hacking away the “paint slag” in heavy chunks.

Most of this was hauled away to landfills. However, some workers, captivated by the rainbow-like cross-sections revealed when the chunks broke, began to smuggle pieces home in their lunchboxes.

How Fordite became “Agate”

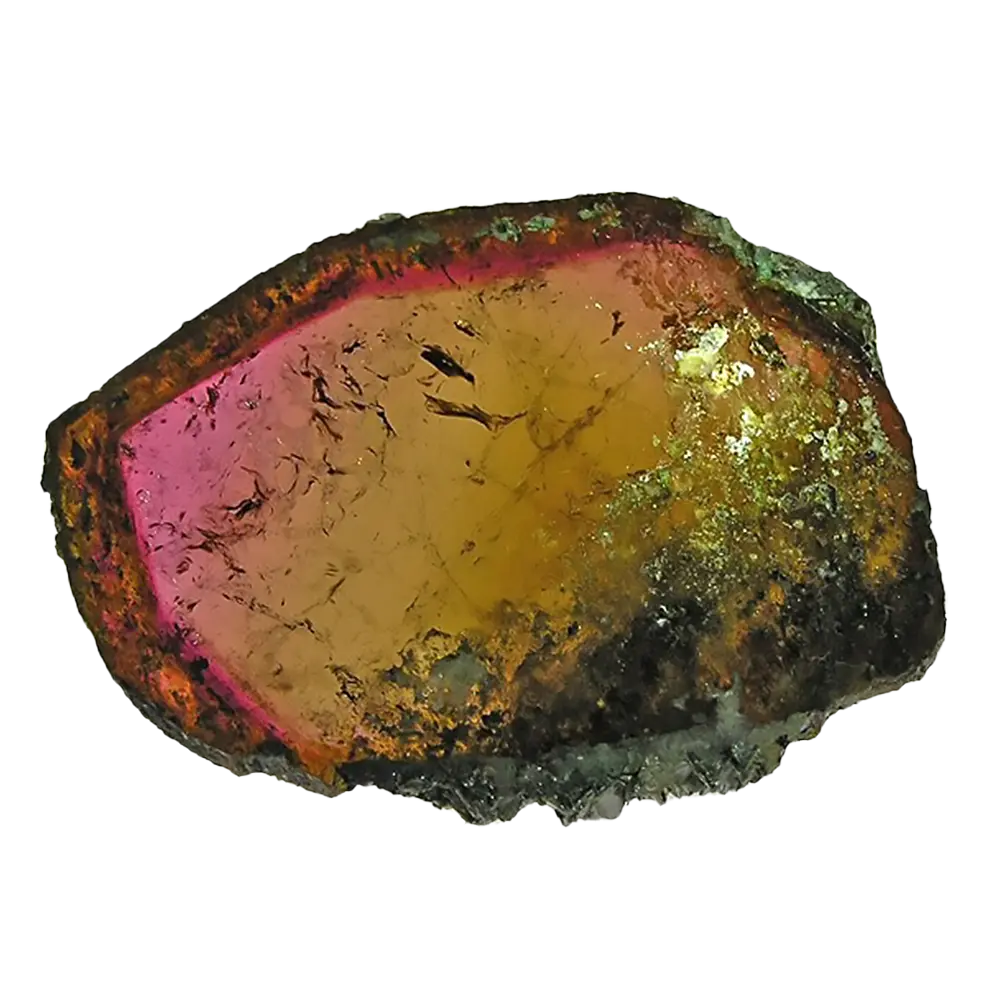

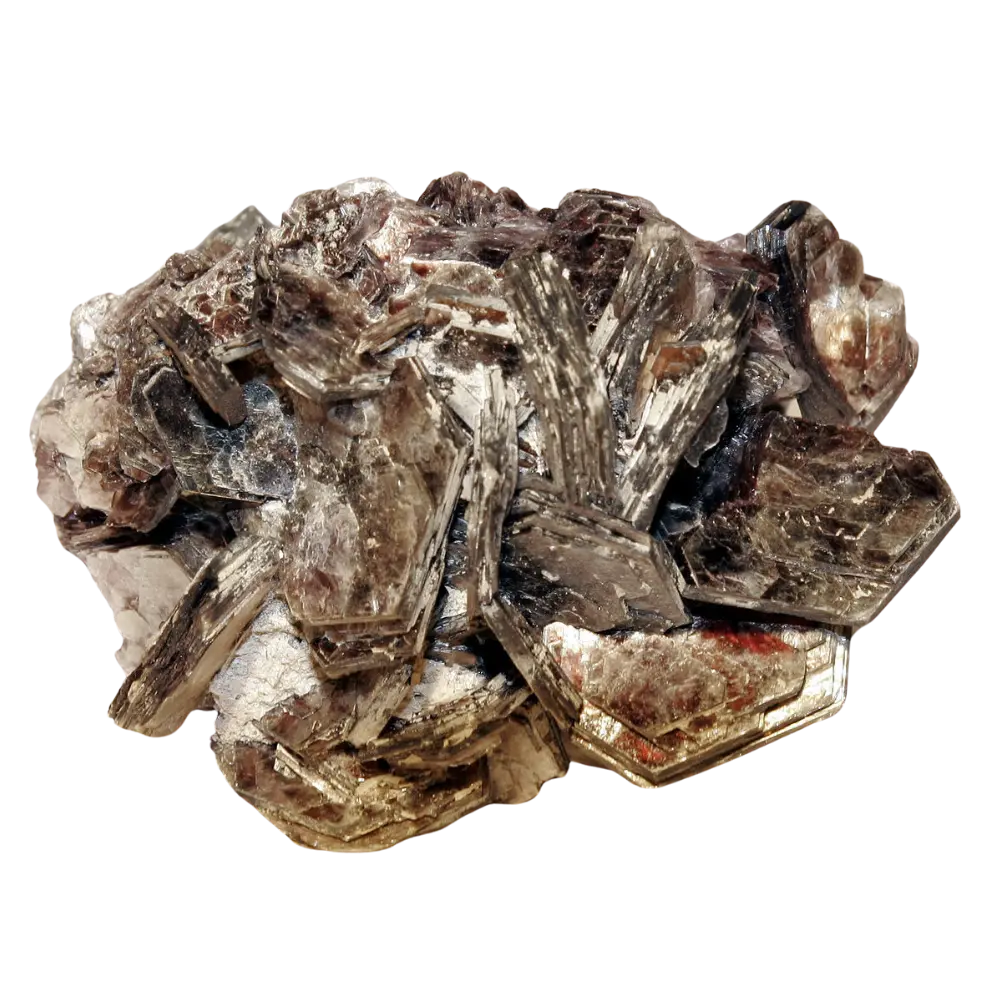

These workers discovered that because the paint had been baked hundreds, if not thousands, of times, it had undergone a chemical change. The solvents had evaporated, and the resins had cross-linked into a material that was surprisingly hard, yet still workable enough to be cut with a saw, sanded with grit and polished to a high lustre.

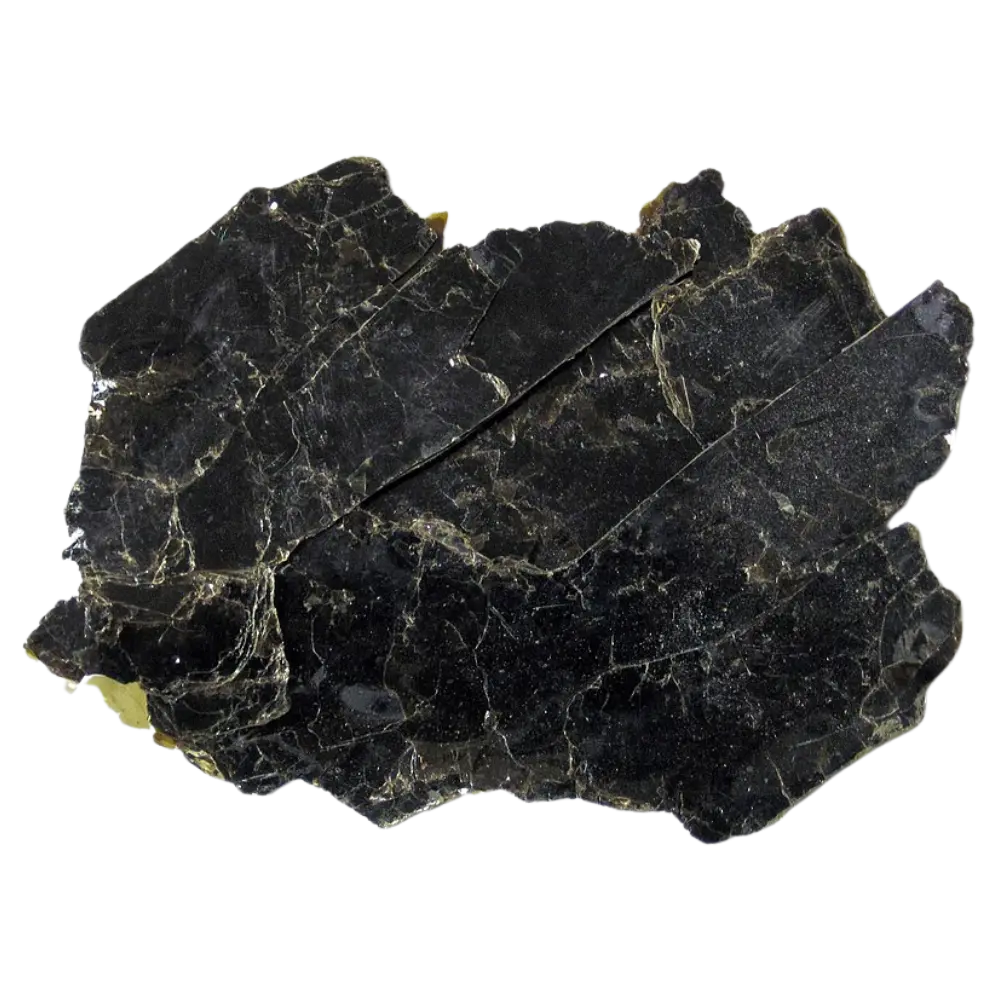

Because the resulting patterns mimicked the banded structures of natural Agate stones, the nickname “Detroit Agate” was born.

The science of the “stone”

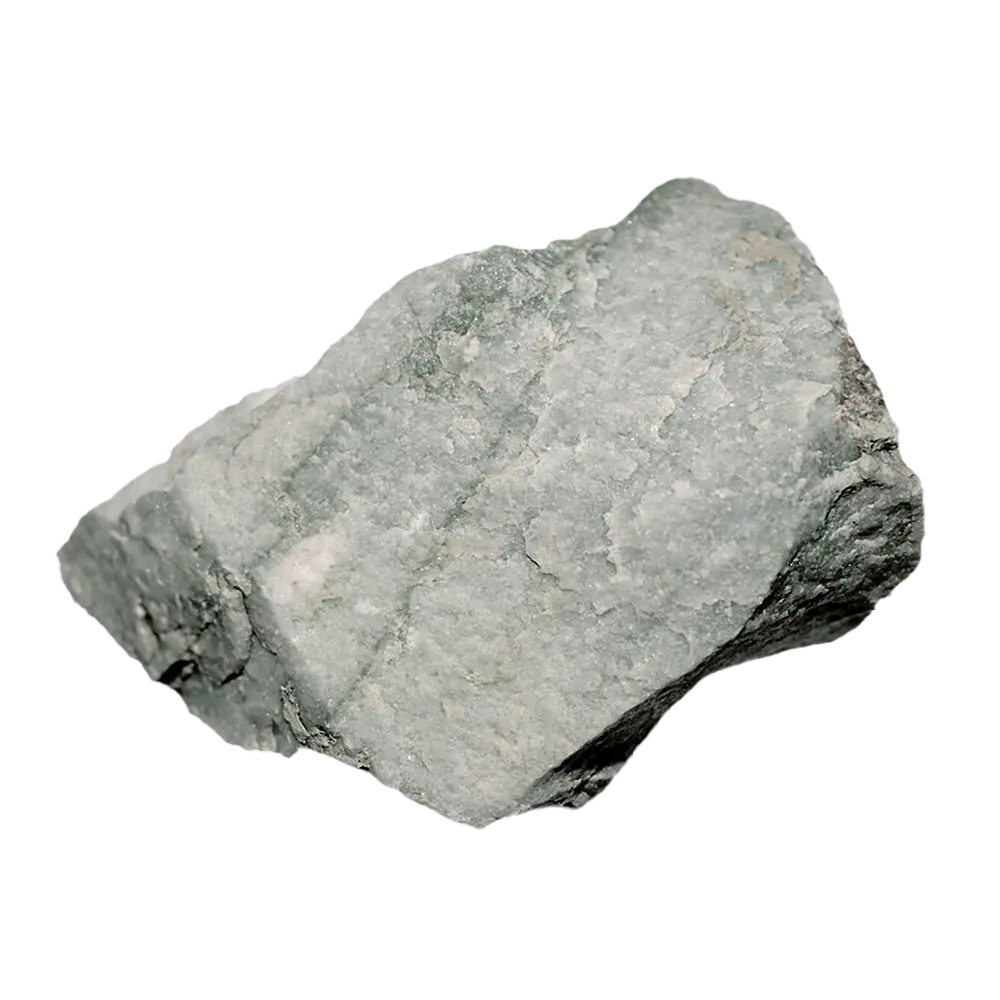

While most gemstones are products of planetary forces, raw Fordite is an anthropogenic lithic material. For lack of a better term, it’s a man-made rock. However, it behaves much differently from modern plastic, and despite its industrial origins, it follows the same fundamental principles we see in natural geology.

Durability and composition

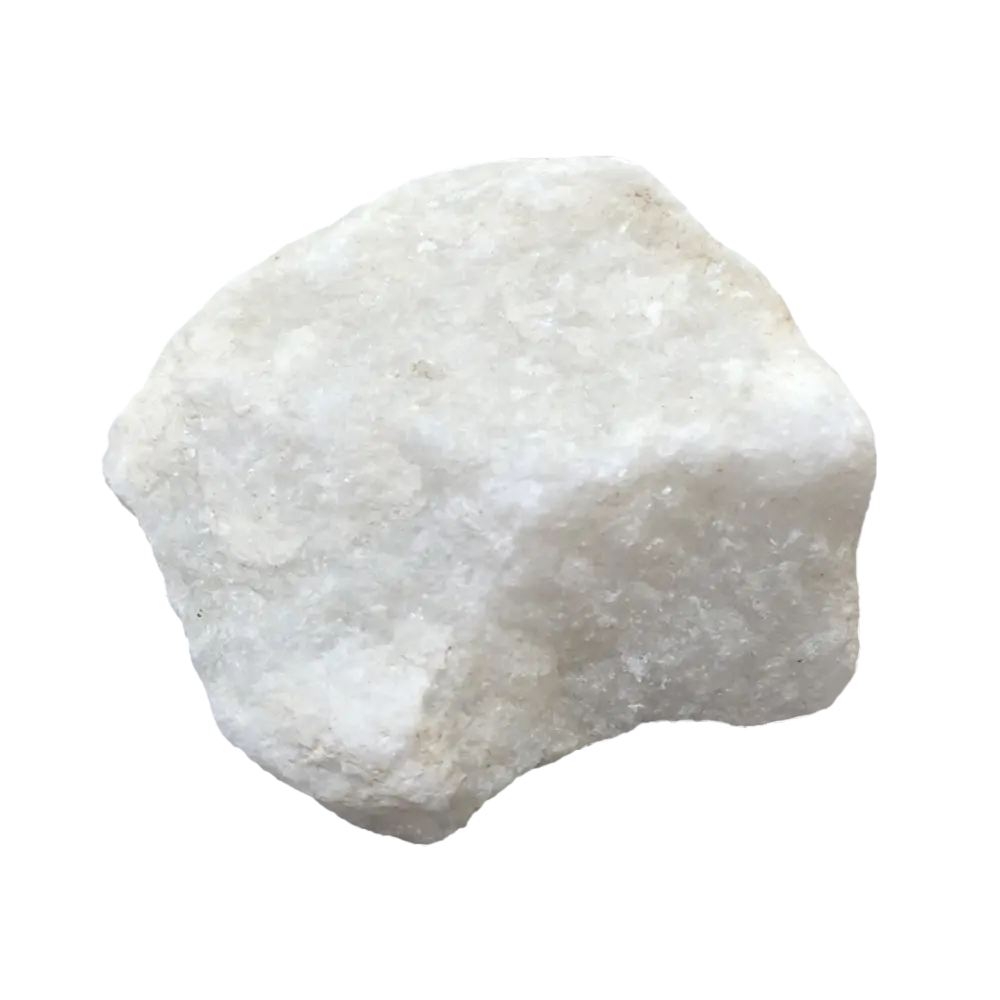

Most vintage Fordite is composed of alkyd enamels or lacquers. Because these were lead-based and baked at high temperatures, the material is quite stable. On the Mohs scale of mineral hardness (where a diamond is 10 and talc is 1), Fordite usually sits around a 3 or 4. This makes it roughly as hard as a copper penny or a piece of malachite.

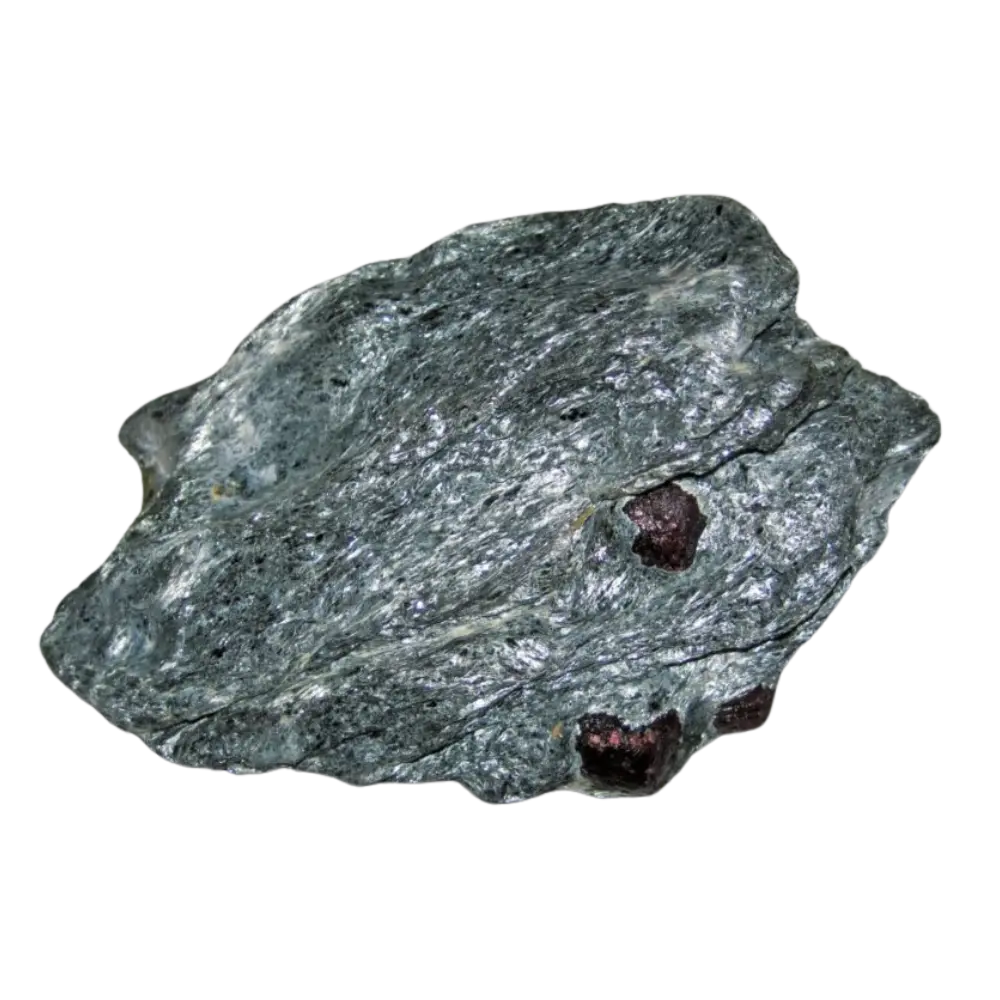

Metamorphism through thermal cross-linking

Natural metamorphic rocks (like marble) form when heat and pressure change a stone’s chemical structure. Fordite underwent a similar transformation in the factory’s bake ovens.

- The process. Exposure to temperatures exceeding 300°F (150°C) triggered polymerisation.

- The result. The liquid resins cross-link into a rigid, 3D network. This “industrial cooking” turned soft paint into a dense, stable solid with a Mohs hardness of 3 to 4, comparable to calcite or malachite.

Reading the “Paint Strata”

In geology, stratigraphy is the study of rock layers. Fordite is a perfect example of the Law of Superposition, meaning the oldest layers (the bottom) were deposited first, and the youngest (the top) are the most recent. In nature, “varves” are annual layers of sediment. In Fordite, each layer of colour represents a specific production shift.

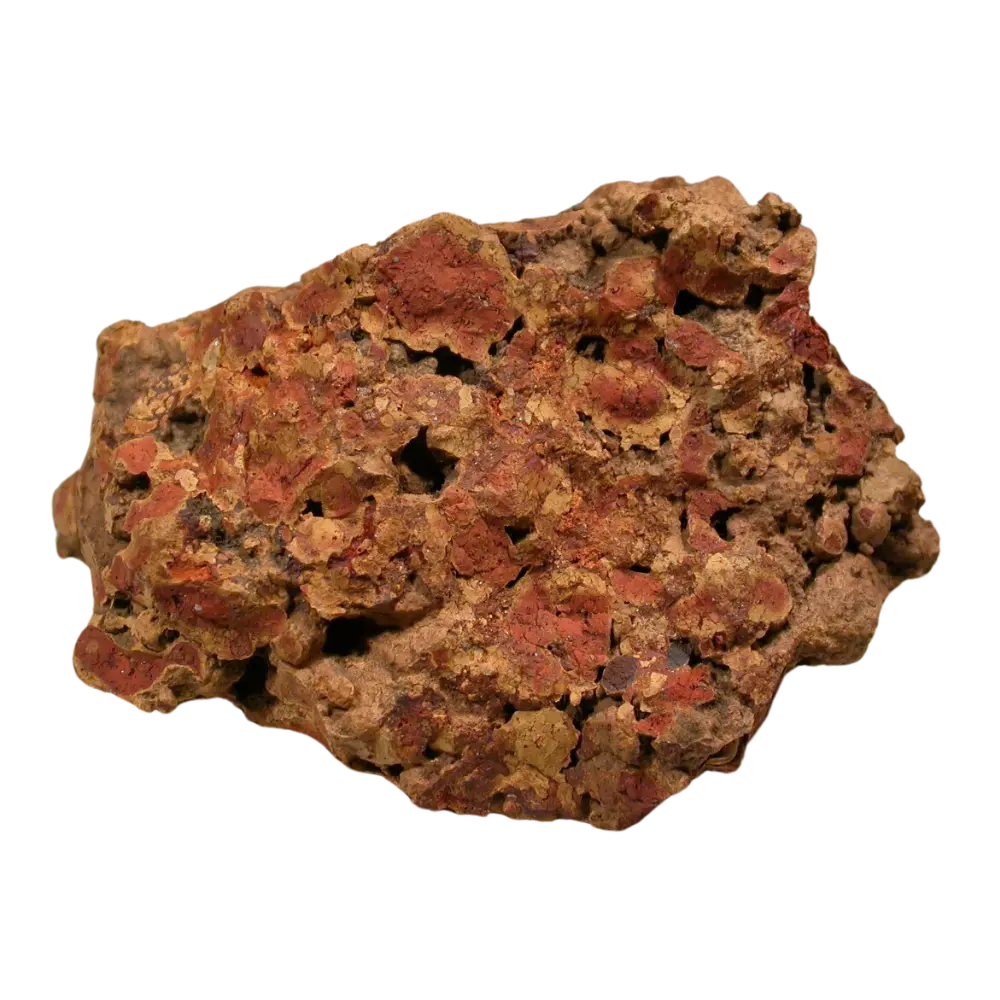

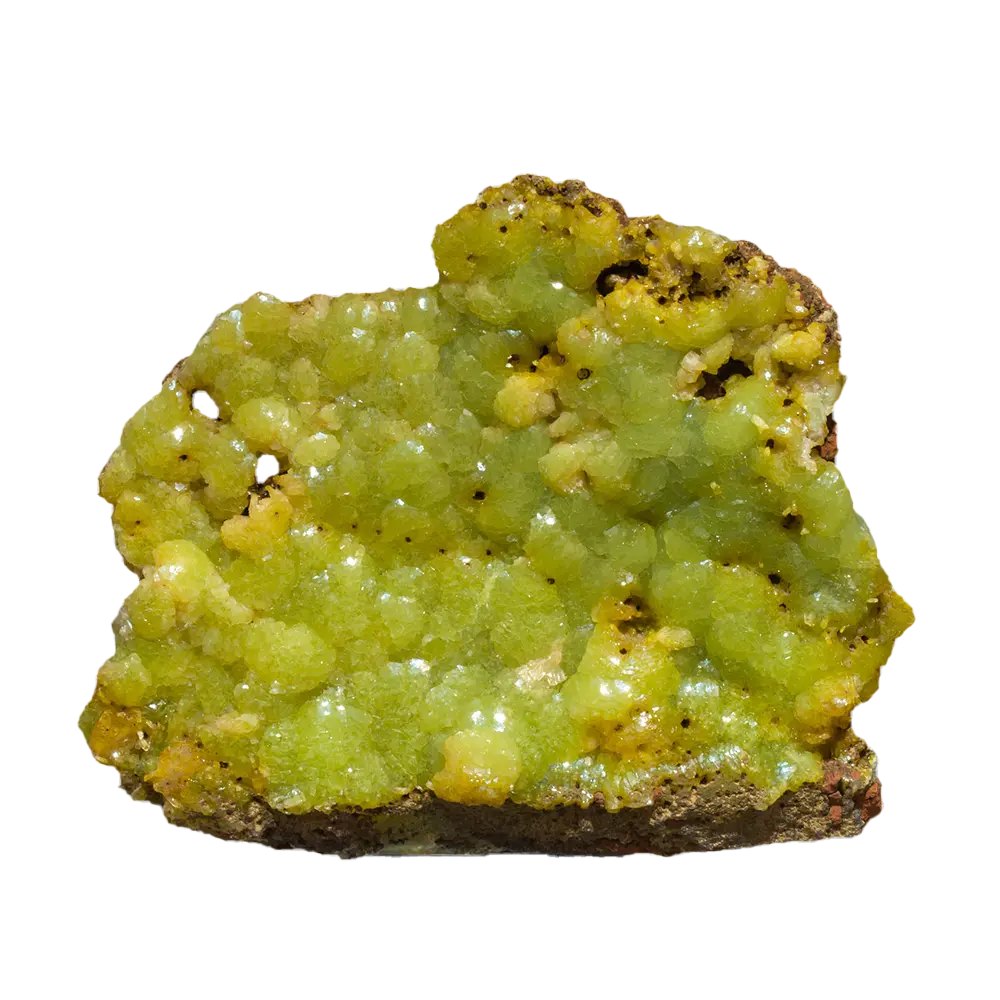

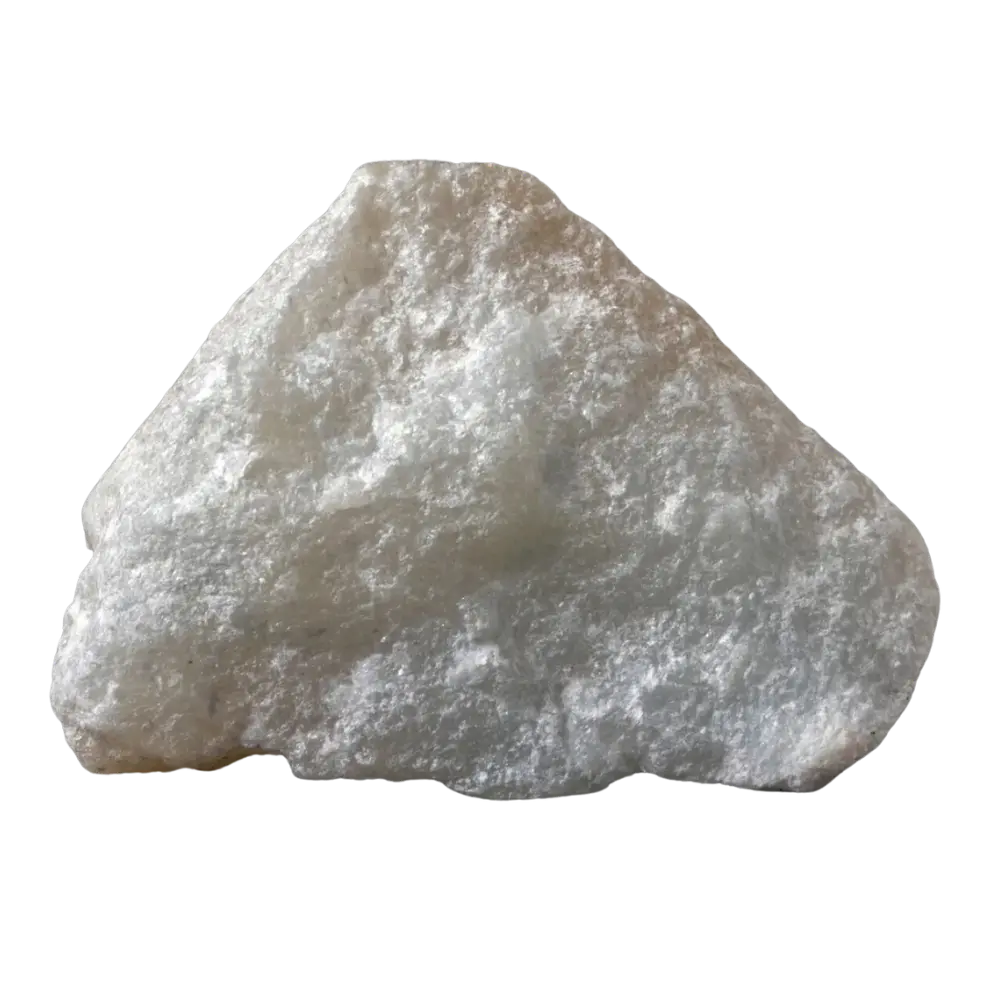

Identifying the “Matrix”

Just as turquoise is often found within a “host rock” or matrix, Fordite colours are often separated by thick bands of grey or oxide-red primer. These serve as the geological background, providing structural integrity to the more vibrant “ore” of the metallic and enamel layers.

Unconformities

Jagged breaks in the pattern indicate “hiatuses”, such as factory shutdowns, strikes or maintenance cycles where the “rock” was partially chipped away before new layers were deposited.

The lapidary process

Cutting the material for Fordite jewellery is an art form that requires “topographical” thinking. A lapidary doesn’t just cut a flat slice; they shape the material into a dome (a cabochon).

- Straight cuts result in “racing stripes.”

- Domed cuts reveal “eyes” and swirling psychedelic patterns as the sanding process dips through different colour “strata.”

- Angle cuts can create a “woodgrain” effect.

These are the fundamentals of how Fordite comes to be and why it takes the form that it does.

How Fordite can be used to track aesthetic tastes

One of the most compelling aspects of Fordite is that it serves as a timeline of American aesthetic tastes. If you know how to read the layers, you can see the history of the 20th century unfolding.

The 1940s were defined by war and utility

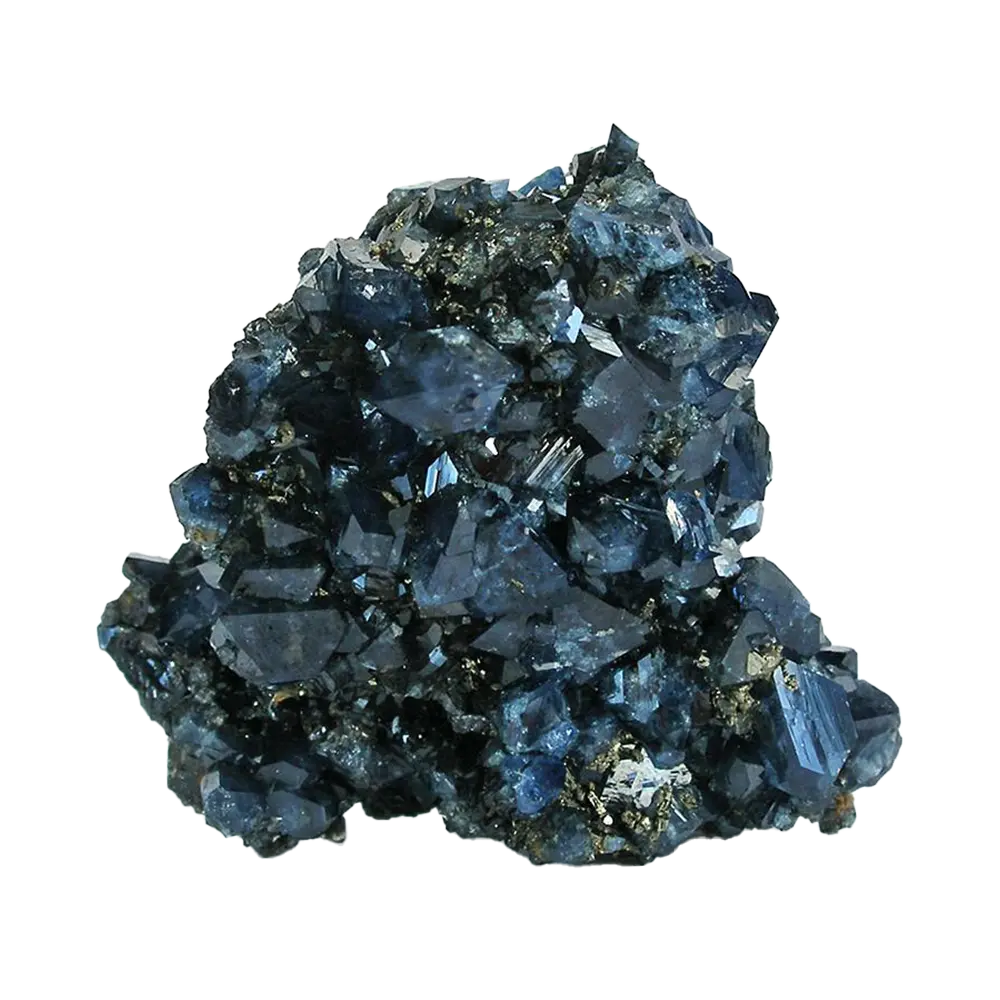

Early Fordite is often characterised by muted, sombre tones. During the war years and the immediate post-war era, colours were practical. Thick layers of black, navy blue, and “olive drab,” interspersed with the grey primer, are commonplace.

The 1950s were the age of pastel

As the economy boomed, so did the colour palettes. This era of Fordite features the iconic “Two-Tone” look. You’ll see layers of seafoam green, flamingo pink and creamy whites. This was the era of the Cadillac Eldorado and the Chevy Bel Air.

The 1960s & 70s were the peak of “Muscle Cars”

This is the most sought-after era for Fordite collectors. As manufacturers competed for the youth market, they introduced “High-Impact” colors. In a single chunk of 70s Fordite, you might find:

- Plum Crazy Purple (Dodge)

- Hugger Orange (Chevy)

- Grabber Blue (Ford)

- Lime Light (Plymouth)

These layers are often separated by metallic flake paint, which became a popular option for the disco era.

Why we don’t make new Fordite

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the automotive industry underwent a “green” revolution. The old method of hand-spraying was incredibly wasteful. Up to 50% of the paint ended up as overspray (and eventually Fordite).

To save money and reduce VOC (Volatile Organic Compound) emissions, factories switched to Electrostatic Spraying. In this process, the car body is given a negative electrical charge, and the paint particles are given a positive charge. The paint is literally “sucked” onto the car, leaving almost zero waste on the tracks.

Furthermore, the move toward powder coating and water-based paints meant that the thick, rock-hard “slag” simply stopped forming. Today, the skids in a Ford or GM plant are mostly clean.

There is no more Fordite being made in the traditional way. Every piece of authentic Fordite on the market today was salvaged from a factory that is likely now a parking lot or a luxury loft.

Global Fordite varieties outside of Detroit

Detroit might be the spiritual home of your favourite Fordite pendant, but other regions have their own unique “species” of Fordite:

- Kenworthite. Sourced from the Kenworth truck plants in the Pacific Northwest. Because trucks are often custom-ordered for fleets, this material often features bold, solid colours and much thicker layers than standard Fordite.

- British Fordite. Sourced from plants like Ford Dagenham or the Vauxhall factories, known for having a very “metallic” look and unique European colours not seen in the US market.

- Ohio Fordite. Often comes from van plants, featuring the earthy browns, tans and oranges popular in the late 70s van-culture craze.

Fordite identification and valuation

Fordite can be expensive. A high-quality “rough” chunk the size of a fist can sell for hundreds of dollars, and finished jewellery can fetch much more, so keep an eye out for these markers of authenticity:

- Genuine Fordite almost always has primer layers of dull grey or oxide red primer between the vibrant colours.

- If you sand or friction-heat authentic Fordite, it smells like old chemicals or a dry-cleaning shop. If it smells like plastic, it’s probably plastic.

- Fake Fordite (made from poured craft paint) is often rubbery. Real Fordite is brittle and “tinkles” when dropped on a hard surface

Some tips for proper maintenance include:

- Avoid solvents in cleaning

- Don’t use ultrasonic cleaners

- Buff with a soft cloth and car wax

With these tips, you can identify and maintain quality Fordite in the long term.

The beauty in the breakdown

Fordite is a poetic material. It is a man-made gemstone born from the “waste” of a world that was moving too fast to notice it. It represents the sweat of the American worker, the evolution of chemistry and the shifting tides of fashion.

When you wear a piece of Detroit Agate, you aren’t just wearing jewellery. You are wearing a microscopic slice of a 1965 Mustang, a 1957 Chevy, and a 1972 GTO, all compressed into a single, swirling heart of colour.